Four Last Songs

Written by Chester Eagle

Designed by Vane Lindesay

Layout by Karen Wilson

Circa 5,720 words

Electronic publication by Trojan Press (2012)

Four Last Songs:

I first heard the Four Last Songs of Richard Strauss in a tiny barrack-room at Cooma, New South Wales, headquarters of the Snowy Mountains Authority. My friend Dale Scott was working for the Authority as an engineer, and I, too, was beginning a career as a teacher in Gippsland, another mountainous region some way to the south. The Snowy Mountains hydro-electric scheme, with its dams, tunnels, and rivers altered in direction, was an undertaking so brimming with post-war confidence that we will hardly see its like again. The engineers and scientists directing it had no thought of failure. Nature could be improved. I say this although only handfuls of people had known the area in the days before World War 2. There’d been skiers, wealthy people mostly, in a handful of lodges, and graziers had brought stock to the alpine grass in the short seasons before they had to take them down again. There’d also been pioneering settlers, like Miles Franklin’s family, who’d known the area as insiders, as it were, and the publicans, drifters, the rural wanderers … but suddenly the Snowy Mountains were the site of a national action, my friend Dale was working there, and I too, with a Volkswagen to pull me through the miles from where I was starting my life, was eager to see what was happening.

Everything was new. In Gippsland, I was starting to find my way as a teacher, mainly because I was growing interested in the region where I’d been placed. In a self-centred way, I wanted to be useful. It was the way I’d been trained to live, my university years were behind me, and the future was there to be created. I think Dale felt the same, and I was curious to know what he and the Authority were doing; they were changing the land, I knew, and it made sense to me.

Dale’s room was tiny, but warm. He had a Volkswagen like mine and he told me there were mornings when he went out to find it, along with all the other barracks cars, covered in snow. ‘At least the VW usually starts,’ he told me, because he, like me, was proud of his little German car, such an engineers’ car in the way it was made, so able to get through anything. Volkswagens had won round-Australia trials, which were popular at the time. They too were a means of taking possession of the country, after years worrying about war. It took me five hours to drive from Bairnsdale to Cooma, and I had to concentrate, because I wasn’t used to operating under pressure for so long. The lights of Cooma were a relief when I sighted them. It was also hard to leave, but that wasn’t in my mind on arrival. Dale always welcomed me warmly, but this time he had something he wanted me to listen to. He wondered if I’d like what a friend had lent him.

This was the Four Last Songs by Richard Strauss, composer of Der Rosenkavalier and much besides, someone I didn’t know much about. I said I’d like to hear this music, and Dale played it to me, volume down so that people in nearby rooms wouldn’t be disturbed. The songs were for soprano but they weren’t like anything I’d heard. The voice produced a line, and it was like the actions of a bird, free to move as it willed in an atmosphere of thought, reflection, and ecstasy when it soared. Birds weren’t always on an up-current, though they used them to stay aloft for long periods. They could dip, come down for a look, before they swooped, swirled, and soared again. They had a freedom humans didn’t have, and we envied them. We were clever enough to make aeroplanes, but that was a different sort of flight, a means of transport rather than a way of being. Richard Strauss? The record cover told me little beyond the fact that he’d written these songs when he was eighty-four, which seemed immeasurably old. It was hard to believe that anyone could do anything at that age, but his music proved me wrong. Eighty-four! I read the words, not very closely, but I could see that they were about a readiness to leave life behind, as something finished, presumably enjoyed but done with.

The opposite of myself, or Dale!

Life, though, the music told us, would go on after its participants dropped out; at the end of the last song there were trills on a flute to indicate the two larks of the poem which will fly, night after night, when the wanderers have found their last sleep. I’d already been moved by A.D.Hope’s poem ‘The Death of the Bird’, so in a way I was being shown its opposite: the larks were carrying the continuity in the Strauss song, and it was the humans who were dropping out. Nothing goes on forever, except time, and life itself, that great abstract, too large to be understood.

Dale took me south, in the morning, towards ‘the regions’ as people in Cooma called the mountain work sites. There was a long slow climb and when we reached the top there were endless layers of blue. These mountains were somehow different from those I was beginning to regard as mine, in Gippsland. They were a little higher, they weren’t turning the corner of the continent, as the ranges of eastern Victoria were doing, they were a central anchor, a pin, a locale, holding Australia in its ocean, making it available to the winds that crossed it and the currents surging against it. I felt we were going to see what held the whole great thing in place.

I was a regular visitor to this region over the next three or four years, even as I was a devoted explorer of the area, not so far away, that had also become mine. In Gippsland, it was the seclusion of the region that had taken me in. In the Snowy Mountains, and their adjacent Monaro, it was the sense of purpose as the Authority, and thousands of workers, recently-arrived migrants many of them, got down to work. Dale was shifted to the regions and I visited him there. He sent me letters telling me how to find him. I started to visit in holidays when I could bring friends, and stay a little longer. We kept up our musical learning. I visited him in one mountain camp to find him absorbed in the 21st piano concerto of Mozart. We played it one afternoon and then, after a look out the window, he told me about two construction foremen who lived in married quarters on opposite sides of the hill. Each was visiting the other’s wife, each had to pass Dale’s barracks, and they did so on opposite sides. Dale had noticed one of the men passing a moment before. ‘How do they know if the other one’s out or at home?’ I wanted to know. Dale laughed, and offered to lend me the record we’d listened to. I said I’d leave it with him, and buy one for myself next time I got to Melbourne.

We were both Melbourne-based in our thinking, we knew we were part of a larger culture, but we had jobs to do, and we had high expectations of ourselves. Not everybody got the chances we were getting, but what were they?

Both Dale, in his engineering, and I in my teaching, were doing what thousands had done before us, but we were doing our work in new circumstances and felt it should be possible to do it better than it had been done before. Dale told me that experienced engineers made mistakes, and it puzzled him, because he was discovering his own abilities. No matter how much you wanted to get something done you should never build on anything but complete objectivity. When people made assumptions he wanted to know how they knew what they said they knew, and as often as not, they didn’t. Their wishes had been parents of their thought. Dale was finding, as he got his career started, that he wasn’t made like that. He was unafraid of the conclusions that the openness of his mind would bring him. People above him in the Authority were beginning to realise that his judgements could be trusted. He was put in charge of shifts when tunnels were being dug, or concreted, and he knew how to tell men to do things, and when to say ‘Not yet’. He was growing into the job.

So too was I, though it was harder, in teaching, to say what was and wasn’t right. The trust of my students had to be won, first, then used for their own improvement, and this wasn’t easy. If I trusted anything it was my own instincts, still untrained, and my sense of language. I loved the home-grown and improvised expressions I heard everywhere in Gippsland, and the rough wisdom of men – mostly men – who’d faced the bush or the mines and had to cope with their lives according to the ideas they’d put together for themselves. And yet, at the same time, and over my shoulder, there was the great tradition, the language and the music, of Europe’s higher classes, who’d expressed, with nobility, simplicity, complexity and the rest of it, all the thoughts that life had brought to their minds.

Life. It was ahead of me, as it was for Dale, and yet both of us were in the thick of it. Sometimes I had to do bus duty, which meant supervising the departure of those who travelled to school from surrounding towns. Most had good homes to go to, some did not, but they were eager to get away, so when the duty teacher told them to line up they did so. One had only to turn from, let us say, the Paynesville line of students to the Bruthen line, to make everyone in the Paynesville line grab their bags, stop pushing, and generally render themselves so well-behaved in appearance that it was my duty to let them go. Yet I rarely came off bus duty, which only took a few minutes, without wondering what the departing busloads had learned, to their benefit, that day. We’d brought them in – compelled them – to learn what? For what advantage that they hadn’t had before?

Many years later, when I’d returned to the city from my mountainous region, I read in a newspaper that an ex-student was in Pentridge prison – a grim-looking bluestone fortress – on a charge of murder. I visited him. A warder sat him on the other side of a grille and we talked. He told me about the shooting, which he claimed was accidental, though I felt sceptical of this, and then he reminisced. Did I remember the Bruthen bus? On his way home one afternoon he’d spotted a dead wombat by the side of the road. He asked the driver to stop, because, he said, he was feeling sick. The driver let him off. He’d scalped the wombat, taken its ears, or whatever was necessary to get the ten shilling bounty, and hitched a ride to Bruthen. He no longer remembered what he’d done with the money but was proud of seizing the opportunity. Nobody else had seen the chance!

I was sad, when I got home after visiting the prison, and followed the trial. My ex-student had fired a rifle at a boating party on an inland lake and had killed a woman. Pure accident, said the defence. A boastful demonstration of his shooting skills and therefore a murder, said the prosecution, and the jury agreed. The judge handed down sentence. I never went to the prison again because what could I say, this time, to my student? He’d had his chances and he’d blown them, taking an innocent person’s life and wasting his own at the same time. It was about as bad as it could be.

All this lay ahead, at the time I was visiting Dale in his mountains, but the signs of later understanding were there, in snatches. We were driving with one of Dale’s friends one day when he told us about an accident that had happened on the same stretch of road. A worker had been showing his wife the area where he worked, and he’d crashed their car into a heavily-laden truck. The man had been killed while his wife, who was pregnant, had survived. Dale’s friend observed, ‘I don’t suppose she’ll ever come back here, but perhaps she will.’ The eucalyptus forest was low, hugging the ground to give itself support against the snow. I felt very raw, immature, too young to deal with such things, and yet I knew they surrounded human life; accidents were always lurking. On an earlier visit, I’d gone into a shop in Cooma one Saturday morning to see what recordings they had of the music Dale and I were exploring, and I expressed enthusiasm for an LP – if you remember them? – of Berlioz overtures. The man in the shop said he’d play it for me … later. I waited for a while, but more people kept coming into the shop and I realised that he wanted me to stay until the shop was closed and then we would have a private audition. I studied the man. He desired me. He was one of what I then thought of as ‘those’. Something in me curdled. He might be but I wasn’t. I paid for the disc and got myself out of the way. I wasn’t married but I had no doubt that I would be, one day, when the time and the right woman came along. Life wasn’t all work, or even the dedication of oneself to a social purpose, such as I and Dale were doing. One had one’s own inner purposes, and a need to shape one’s life from within. People who couldn’t do this were lost: they made trouble for themselves and those near them. People without an inner need, well managed and well satisfied, were a danger to themselves and anybody foolish enough to get too close.

I made many trips to Dale’s area, which I began to think I knew well. As I said before, I took friends with me on occasions. Once it was Simone, described elsewhere in these memoirs (see Keep Going) who came. We entered the region via the Geehi Walls, and found the Geehi Hut, following Dale’s instructions. There we camped for a couple of days. It’s hard, looking back, to know what we gained from being there. I think, perhaps, it was a sense of the hugeness of the region, and its otherness from human purposes. One could swim in its rivers, drive about, or walk, all as a measure of one’s smallness and unimportance. For all the scale of the Authority’s undertakings, humans didn’t matter much. There was no indication of who’d built the Geehi Hut, though the Authority had left a couple of their own pre-fabs recently, and Simone and I used these as our sleeping quarters. I wonder, now, how much I actually saw of the places we visited because Simone commented that I drove in the same way as her estranged boyfriend. He, she said, drove as if obsessed, concerned with his car and its cornering, its performance, its speed, rather than with the countryside he was passing through. She had only to say this to make me know she was right; that was how I was driving. I was still caught up inside myself, I wanted to be where nobody had been, I wanted to do things I hadn’t done before, I was so concerned with discovering myself, unable to realise that other people wanted me to be secure so that I was unnoticeable. That was what people were like, when they matured, and it was a stage I hadn’t reached.

And yet I did care about the mountains, with their endless forest coverage, and their occasional eminences. Dale showed me Mount Jagungal one morning, telling me he’d been there with a bushwalking party. It was grand, distant, and I envied Dale’s group for getting themselves to it. I wanted to add it to my list of places where I’d been. It seems childish, now, to think of myself ticking off these achievements, as if getting something done somehow added to the quality of the person who’d done it when commonsense might have told me that if you did things in a rush, without understanding, then you’d hardly done them at all.

I remembered that when Simone and I had been at the Geehi Hut, we’d had a caller one afternoon. We were sitting at the table when a stranger walked in. He’d walked, he told us, from an Authority camp some miles away. We were not in the slightest interested. We were talking about a novel Simone had been reading in which, as she told me, the central figure had developed the ability to go travelling, as it were, inside his own body. Needless to say, fiction being what it is, he went exploring the activity of intercourse. Something about this caused Simone to quibble. This was what we were talking about when the intruder arrived. Since we were drinking tea, and he was lonely, we offered him a cup. He drank, and seemed ready to sit all day. I was furious with him. Heavens above! We’d come to a place as remote as this to get ourselves lumbered with someone we didn’t want! I told Simone I was going for a swim. I went.

The Geehi River was cold, but the day was hot, and the swim delightful. I went back to the hut. The man had gone. ‘He made a pass at me,’ Simone said, ‘but I told him it wasn’t on. He left after a while. I suppose he’s on the track, now, to his camp wherever that is.’ I had the grace to be ashamed. I’d left Simone to deal with the man, he’d pestered her, and I’d been in the river, swimming happily. I’d been so concerned by my own displeasure at having responsibility for this lonely wanderer who’d found two people on whom to unload himself, that I hadn’t thought of him as a sexual threat to Simone, and yet she, I saw, had been aware of this side of him all the time. I had such a long way to go before I could see myself as any sort of man at all!

Dale took leave, returned to Melbourne, then let me know, via one of our letters, that he’d found a partner, they were engaged, and he would soon be letting me know the date of their wedding. His brother, whom I knew well, would be his best man, and would I act as groomsman? Marriage was the major step in anyone’s life because it was, as I then believed, a lifetime undertaking. There was such a thing as divorce, but marriages produced children, and their arrival fixed one in the endless line of generations. The liberty of youth didn’t last, and Dale was ready to go on. I was envious, and wrote back to congratulate him. I referred to the last of the Strauss songs, where the flute trills make us think of larks which will live on, while the wanderers realise they are in more than a mood: they are dying. Until that moment comes, I said to my friend …

Dale was amazed, and grateful. The wedding took place at Christ Church South Yarra and there were associated parties. The second of the bridesmaids was single and I felt that one path open for me was to form a relationship with her; the bride herself was the sister of Dale’s brother’s wife, stranger things have happened. But I was too strict, too stubborn, to drift into an arrangement of this sort, though people did such things. I wanted to live according to my ideals, though I hardly knew what they were!

I was living at the time in a huge house in Bairnsdale, with a large and comfortable room overlooking the valley of the Mitchell, and I had a gramophone to play the music I loved. One evening there was a knock and the door opened. It was Eva Kracke, the proprietor, asking about the music I’d been playing. Mrs Kracke, as I’ve related elsewhere (see So Bitter Was My Heart), loved to sing, and her ear had been caught by Lisa Della Casa. I showed her the record cover, then put on Im Abendrot, at high volume. Once the voice began to soar, Eva filled with joy. It was what she dreamed of being able to do. She stood in the doorway, a big woman, swept away. I’d always been fond of her, in a patronising way, but she was showing that her ability to respond to music was as great as mine. She thanked me profusely when the song ended, and left me, holding the record as if I held something magical in my hand.

As I did. It was not lost on me by then that all the great sopranos of the world wanted to record the Four Last Songs, and it was impossible not to admire them but the fact was that I thought that Lisa Della Casa had an advantage over those who’d come after: she hadn’t heard them before she sang herself. The tradition gathering around these songs was, at least in part, her creation. I had a score of the music by this time and it seemed to me, also, that the floating, the cloud-skimming, and the effortless world-consideration from high above in her rendition came more naturally to her than to her perhaps more famous rivals. Many listenings had engraved her performance on me. The idea that one might welcome the end of one’s life as inevitable, even beautiful, had become natural to my thinking. In the mountains to the north there was a place – Mount Baldhead – where one could see the river that rose at one’s feet moving towards its end in the Gippsland Lakes, and then the sea. From the school where I worked, one could look back and see Mount Baldhead, where the Nicholson River had begun. Now this journey, to which I had attached the concept of life as something complete in itself, had gained another dimension. The journey seemed a little less important, the traveller a little more.

Or travellers? I wasn’t married, and I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be because I wasn’t sure what it would mean. Marriage was an ideal state, for me, yet I was aware that many men – far too many to be ignored – saw it as taming a man, reducing him, taking away the freedom that made life worthwhile. How could I think this, though? A couple of weeks after Dale’s wedding, he sent me a note. He and his partner had spent several days bushwalking in the Grampians at a time when it was a riot of wildflowers, they’d camped in a tent and been very happy. Their next plan, he said, was to go to Europe, which neither of them had seen, and explore. Three months passed and then another letter came from Germany. They’d seen a performance of Die Meistersinger and it had been more marvellous than they’d dreamed possible. Germany’s musical tradition had picked them up and they couldn’t wait for more. Teaching far away in Bairnsdale, I knew I was on the fringe. Gippsland was a fascinating place but as far as I knew at that time it had had almost no expression of itself and even if it had, the few offerings it could muster wouldn’t amount to much. Nothing that I knew about the place where I was living required the sophistication or polish of the music that I loved from Europe. Gippslanders were like most Australians in forgetting, or not taking very much notice of their past.

Life, for most Australians, had still to be shaped in any important way by art. This may have been why I was still absorbed by things emanating from Europe. People like me, who thought that everything had to be shaped, defined, inside the mind, had to think in a European way because our own country hadn’t given us the means to do otherwise. I was always reading books, and I played music all the time. Eventually, I began to write. It was my way of putting thought, as opposed to ambition, sexuality, or endless work, at the centre of one’s function. Understanding, I felt, should be the ruling force in human life. I wanted to be able to make sense of what happened to me, and this required that definition, the closest possible approximation of words and meaning, should be of central importance. I was maturing, I married, I had children. I became responsible for myself in being responsible for others. I was not religious, I would have said, so my secular understandings had to enlarge in order to cope with all the extra things I found myself thinking about. Human beings can’t shut out the larger questions, though we may try. At some stage we have to give ourselves answers. Our children ask us things. Teachers, such as I was, face questions every day. Education wavers between certainties and uncertainty. It’s the nature of the job. Years passed, and I found myself writing a novel (The Garden Gate) in which I wanted the shape, the form of the book, as well as its underlying currents, to embody my philosophy of life. I drew on everything near to me, my own life, people I knew, things I saw going on around me. The philosophy of the book would be innate, drawn from the things it showed, or so I determined. I spent ages in preparation for the writing and did interviews with people whose occupations were different from my own, so that my characters could perform these social functions easily. I wanted to be able to live inside my characters, I wanted to render historical processes which I had perceived in lives other than my own. And of course I wanted to make it clear to the reader that that was what I was doing. I began the book, I got it far advanced, and then, to create a moment of a certain sort, I needed two of my characters to see each other in a newly-intensified way. They would hear the Four Last Songs. I couldn’t make an orchestra sound, in my pages, but I could quote the German … and I would have to put a translation in the footnote, because I could expect no more German from my readers than I had myself, and that was very little.

Or was it? I looked closely at the poems, and felt that after hundreds of hearings I had a fair idea of what they meant. I pulled out a couple of translations, meaning to use one of them as my footnote, but they simply wouldn’t do. I couldn’t have told you what was wrong with them, but my instincts rejected them. What to do? I rang a friend in Canberra, whom I’d worked with some years before, her language skills being greater than mine, and asked her if she would give me a translation if I sent her the poems. She said she would. Then a strange thing happened. I went to bed thinking that I’d solved the problem by handing it to someone else, but I hadn’t. I woke in the middle of the night, with a translation buzzing in my mind. I went to my work room, where I’m writing now, and scribbled down the words in my mind. They looked good in the morning, so I used them. This is what I wrote, in the middle of that night, back about 1980:

The garden is already mourning. A cool rain is falling on the flowers. Summer, a ghost of his former self, shudders at his approaching end.

Leaf by leaf, his glory falls from the trees. Surprised at his own weariness, he smiles; when the garden wakes, he will be gone.

For a long time he lingers, trembling by the roses. Languorously, longing for rest, he shuts his pallid eyes.

I can’t tell how these words will affect the reader, but they are my version of ‘September’, by Herman Hesse, second of the four songs. It wouldn’t be correct to call them a translation, since I didn’t, and don’t, have the German to make a translation. They are a rendering, in English, of what the music brought to my mind. I finished my novel, pleased to see its threads coming together in the last chapter, and then, and as usual, I wondered where the book’s completion had left me. One has always to go on, and the first step is to locate where one has been left. Every book finished moves the writer from somewhere to somewhere else, and these somewheres aren’t easy to locate. We take parts of our lives and in making them comprehensible for readers we lose them for ourselves. I, for instance, wrote my childhood into Mapping The Paddocks, and it’s no longer mine. I’ve objectified it, and in doing so have moved it away from myself. If you ask me, today, about my childhood, I can only dig out the book and read what’s written there. The experience, the lived life, has become words on a page. This is a loss only for the author, since the world is a little richer for the transformation. We can, if we wish, laugh at the way the world loses people but gains in words, and memories, until they too are let die because nobody remembers them any more. Books are tombstones, if you want to see them that way, or gardens, ready to be brought to life by their readers. There are so many ways of seeing the world, all rendered into books, so that a room, a library full of them is an endless encyclopaedia of the ways whereby we can use up the life that’s been given us.

And, the human race being what it is, the world is endlessly full of people setting out on their own little voyages, regardless of what’s happened in the years before them, casually or carelessly ignoring the past because they can see a future belonging to them. So my practice of the art of writing forced me to think of the similarities and the differences between us all, from Johann Sebastian Bach to the latest African dictator. Lives vary, yet even their variations make them alike. They begin, they end. Fortune favours some, and frowns on others. Luck flows every which-way, and rarely stays consistent. Dark forces gather against us, then some sort of light spreads over our troubles …

Und die Seele umbewacht

Will in freien Flugen schweben,

Um im Zauberkreis der Nacht

Tief und tausendfach zu leben.

Strauss put a violin solo in front of that passage, then brought in his soprano. Singers are fortunate because humans shed most of what makes them disgusting when they sing. We lose our ordinariness, our pedestrianism, and become the marvellous entities we want to be. The child dresses up to transform herself, while adults must have it done for them, and it’s art, most especially music, that does the trick. The world changes when music sounds. Parts of ourselves that were hidden can come to the fore. Eva Kracke, knocking on my door, was asking to be allowed in. I was already there, for the moment, because I had access to the recording Dale had introduced me to, a couple of years before. When I played Eva the Lisa Della Casa recording of Im Abendrot, Dale and his wife were already in Germany, where Die Meistersinger was waiting. Richard Strauss, while still in his twenties, had written Death and Transfiguration, and as an old man, needing to produce something summative, had taken its final theme and used it in the songs that had such an effect on me.

This is perhaps the wrong way to talk about the songs, that is, as something separate from oneself. Music has a way of becoming part of us. Music enters our understanding, helps it do its work, then takes it over. Music connects us with the world, the people, around us. Singing joins us. Football crowds like to sing, political crowds too. Something inward becomes outward when we sing. Most of us can’t sing very well so we have to accept popular songs as the joining agent, until …

… a song that’s good enough to lift us out of ourselves comes our way, and then we’re truly transfigured, whether we want to be or not. The fact is that none of us performs at the levels where we might, we’re somewhere below our best until we’re lifted onto the plane where we’d like to be but have never known how to get there, and then we too can soar and dip, can move like birds in air. For most of us, this is likely to be experienced when we feel uplifted by love, desire and fulfilment, but Richard Strauss, who wrote love music too, came good when most of us are limping, at the very end. How strange. When his turn came, and he lay dying, he told someone that dying was just as he’d written it in Death and Transfiguration. At the beginning, he had foreseen the end. The mind has rights – rites? – of travel. It likes to leave our bodies, from time to time, and look around. What does it see? What does it hear? We don’t need to press ourselves too hard for an answer because we’ve been given it. Summer, as conceived of by Richard Strauss, is no more, no less, than you or me:

For a long time he lingers, trembling by the roses. Languorously, longing for rest, he shuts his pallid eyes.

The writing of this book:

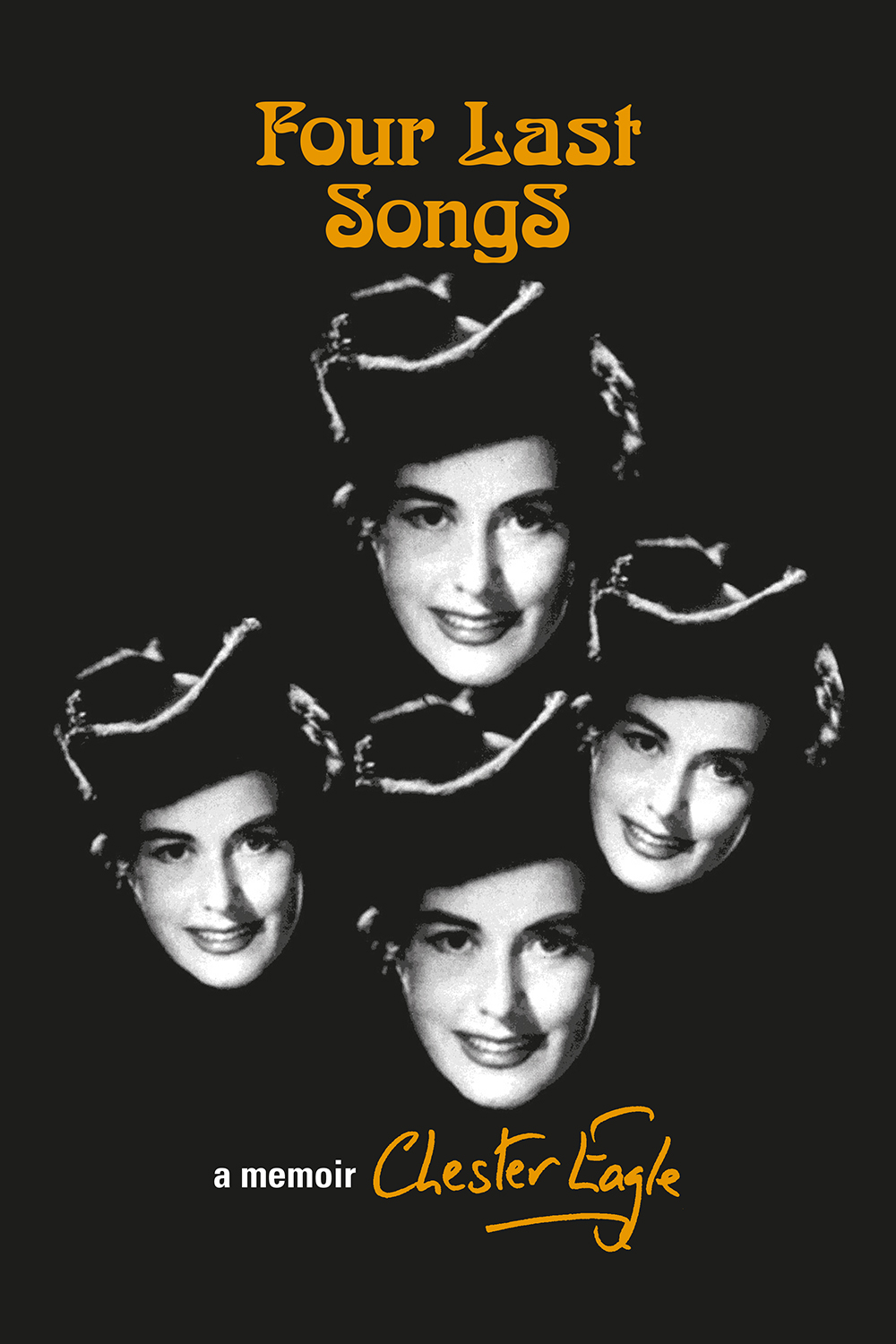

Another pair, something I seem to like doing these days. The relationship this time is more discursive than with Chartres and The Plains, but both Four Last Songs and The Camera Sees … range across a life’s span. The life in question, which happens to be mine, is considered, first, from a musical vantage point, then reconsidered from the point of what, and how much, can be revealed by a camera portrait. Not so very much really, in the case of the camera. I think what’s common to the two memoirs is their concern with how little we understand when we are young. The camera looking at the young Chester may show him better than he knows himself – this is an open question, I suppose – but it cannot know, any better than he does, what’s to happen to him, and as for the previous memoir, the young man who listened to the German composer’s late songs simply had no idea that they would become as a permanent point of reference in his viewing of the world.

How could he know anything like that?

Another thing I need to say is that I am growing old and can no longer produce such complex works as my novel Wainwrights’ Mountain. I can’t see such things ever coming again. I’m too worn out to produce anything so big, but then again, I don’t need to. I wrote that book when I needed to unify my vision of the world, and that’s been done. Now I can enjoy the liberty of producing fragments, confident that they fit together in some way, and offering them to readers to examine and see what they can find.