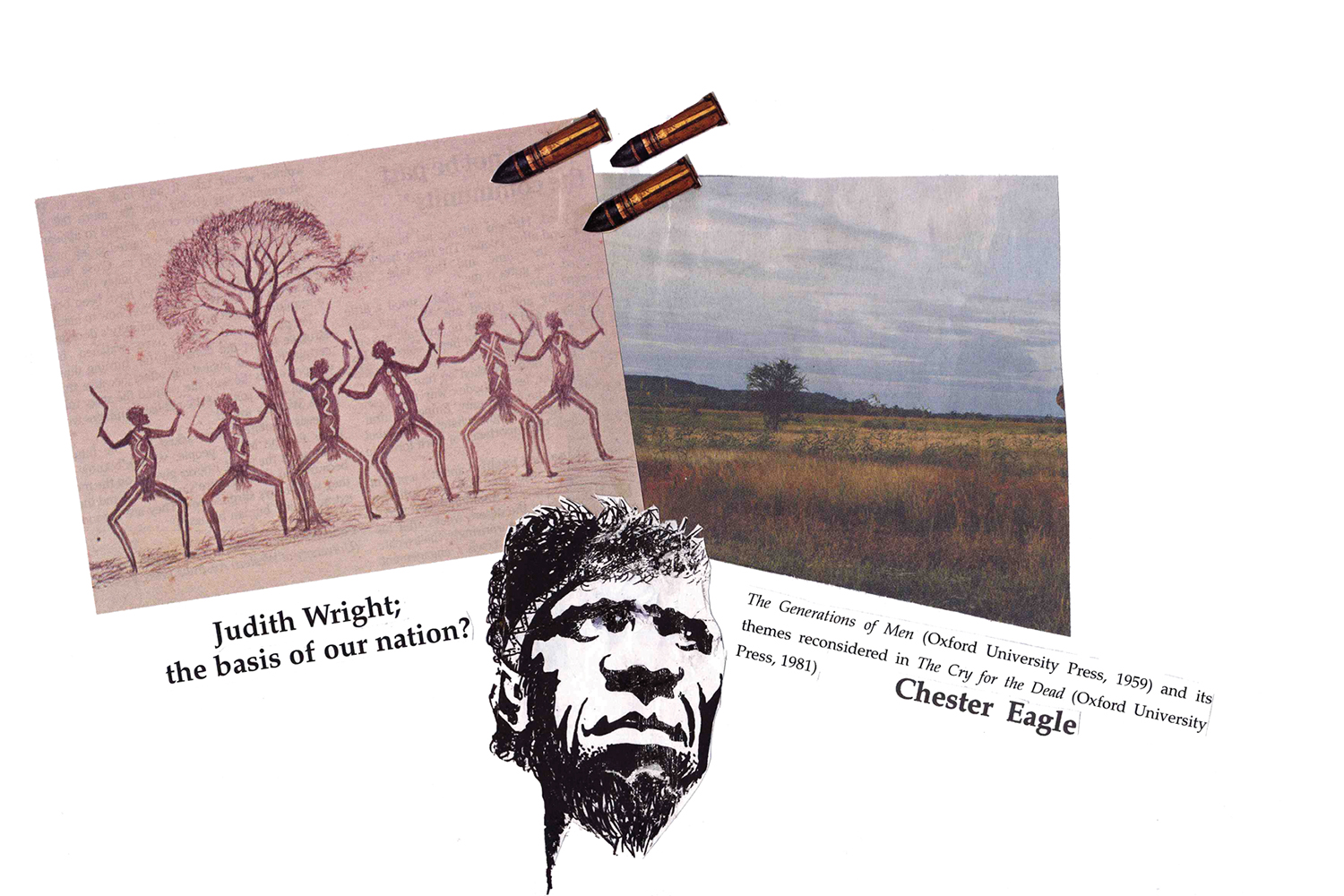

4. Judith Wright; the basis of our nation?

4. Judith Wright; the basis of our nation?

The Generations of Men (Oxford University Press, 1959) and its themes reconsidered in The Cry for the Dead (Oxford University Press, 1981).

Judith Wright; the basis of our nation?

Judith Wright is one of our finest poets, and I hope to say something about her poetry elsewhere in this series, but this essay concerns two prose works by her, both of them about an earlier generation of her family and what it was they did in opening up the land in New South Wales and Queensland.

Opening the land? It was already open, was it not? Hadn’t the black people lived on it, in it, inside its many meanings, for sixty thousand years, or some such stretch of time?

Yes, they had, but this view of the occupation of Australia is not widely admitted by the later, invading, society, which preferred until recently to describe the country as terra nullius. How shall we translate? Nothing-land? Nobody’s land? It isn’t true, is it, but it was a convenient fiction.

Using the word ‘fiction’ opens up the question of the role of stories in human history. Everyone knows the saying that history belongs to the victors. Those who lose battles have their stories, their versions of what happened, wiped away. Accepting this idea for the moment, and applying it to the first of the two books under consideration, it seems to be true enough to explain what Judith Wright has to say. The Generations of Men is about her forebears, in particular her grandfather and grandmother, Albert and May. It’s a story of heroic struggle, it’s about the opening up of the land, it’s about a man who worked too hard for too long, and died too soon to see fulfilment. This arrives only after more years of work and calculation, and it is achieved by a woman whose endeavours are just that little bit less over-reaching, more carefully considered, than her husband’s were. [read more]

Introduction:

In 1981 Patrick White published an autobiographical book called Flaws in the Glass; the Melbourne Age commissioned two reviews, one of them from Hal Porter, who said, among many things unflattering to ‘Mr White’:

Writers of my sort can be said not so much to read as to examine another writer’s work rather as one car freak examines the vehicle and driving of another car freak. One says, “Splendid vehicle! Superb driving!” Or, “Nice vehicle! Ghastly driving!” Or, “Can’t stand that kind of cumbersomely pretentious vehicle! And what bewildering and erratic driving!”

Hal confesses that the third attitude is his to the novels and plays of ‘Mr White’. I will say no more at this point about Mr White or Mr Porter, but I quote this comparison of writer and car freak because in the essays that follow I am the freak who comments on others of his kind. I know I can’t see my essays as others will see them but I imagine some readers accusing me of many things, and others, well trained, perhaps, in one or another school of literary or social criticism, who will think my observations no more than shallow or ignorant. To such people I can only say that these essays offer whatever it is that a fellow-writer can offer, and don’t pretend to offer anything else.