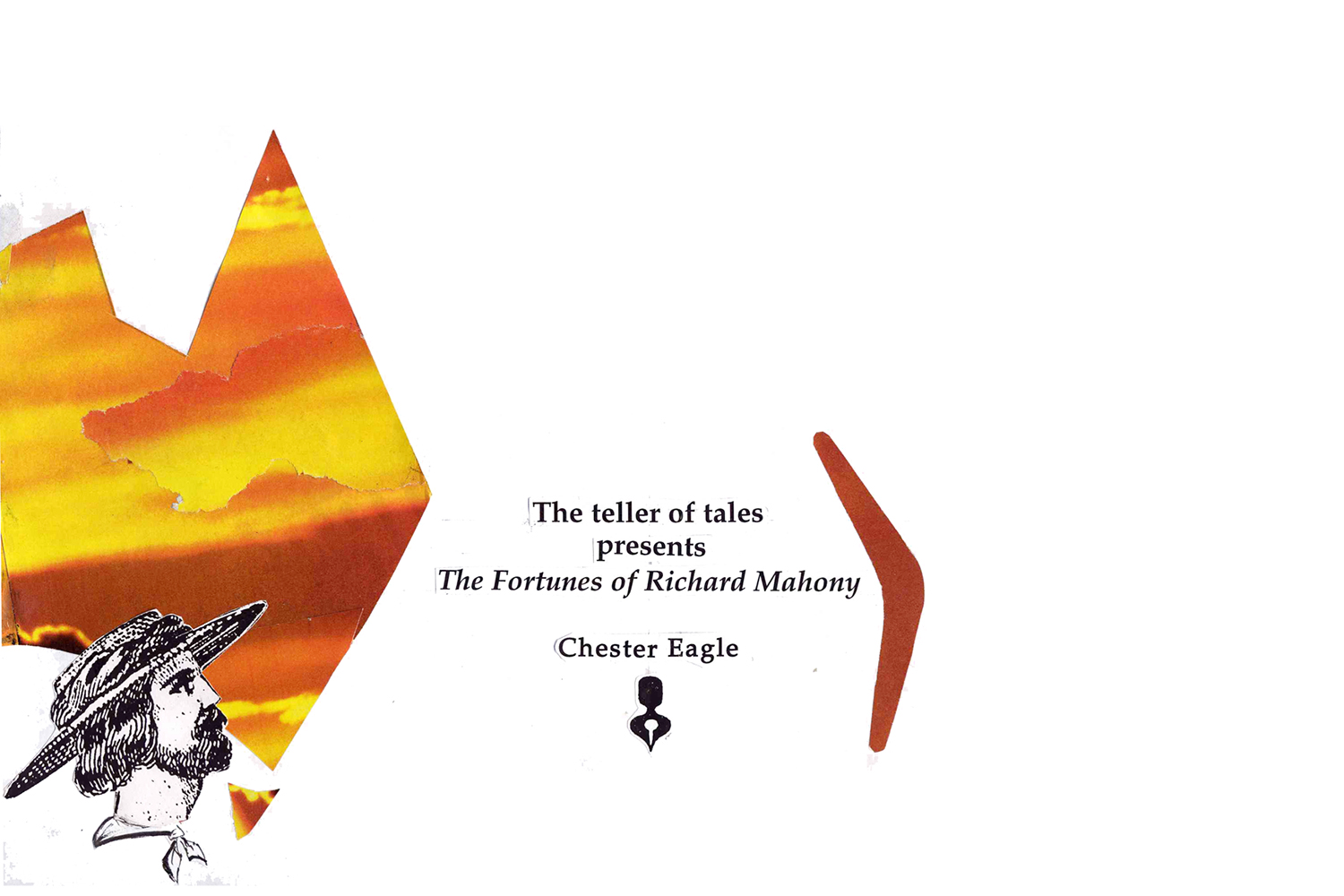

7. The teller of tales presents The Fortunes of Richard Mahony

The teller of tales presents The Fortunes of Richard Mahony:

The Fortunes of Richard Mahony is widely regarded as one of the best books written by an Australian, although it is worth remembering that its author left for Europe when she was eighteen, after which, apart from a six week visit to check details of the huge work she had in progress, she never saw the country again. Yet Australia fills the masterpiece which HHR has given us, though it is Richard Mahony who is the book’s principal subject, not the country he adopted, as a young man, in the hope of leaving with an easily-gotten fortune. Mahony – and his wife, Polly, later known as Mary, without whom he was always incomplete – Mahony’s fortunes are what we follow, somewhat like the miners in the early pages, pursuing a lead in hope of striking riches, only to find it petering out in dull earth, yielding nothing. Mahony is the subject, and even Ireland, his homeland, and England, though powerfully presented when the narrative reaches them, are background, stage-setting, to the lengthy, indeed epic, tale.

The Fortunes of Richard Mahony is HHR’s highest achievement, yet, in the presentation that I wish to make, it rests on a prior, less obvious achievement internal to the writer: I mean the almost statuesque objectivity, wide, even vast, in its scale, which she brings to her subject. If we look at HHR’s writings apart from the famous trilogy we will be able to pick out a few suggestions, not much more than that, of how this objectivity was gained – gained, because it had not always been there. [read more]

Introduction:

In 1981 Patrick White published an autobiographical book called Flaws in the Glass; the Melbourne Age commissioned two reviews, one of them from Hal Porter, who said, among many things unflattering to ‘Mr White’:

Writers of my sort can be said not so much to read as to examine another writer’s work rather as one car freak examines the vehicle and driving of another car freak. One says, “Splendid vehicle! Superb driving!” Or, “Nice vehicle! Ghastly driving!” Or, “Can’t stand that kind of cumbersomely pretentious vehicle! And what bewildering and erratic driving!”

Hal confesses that the third attitude is his to the novels and plays of ‘Mr White’. I will say no more at this point about Mr White or Mr Porter, but I quote this comparison of writer and car freak because in the essays that follow I am the freak who comments on others of his kind. I know I can’t see my essays as others will see them but I imagine some readers accusing me of many things, and others, well trained, perhaps, in one or another school of literary or social criticism, who will think my observations no more than shallow or ignorant. To such people I can only say that these essays offer whatever it is that a fellow-writer can offer, and don’t pretend to offer anything else.