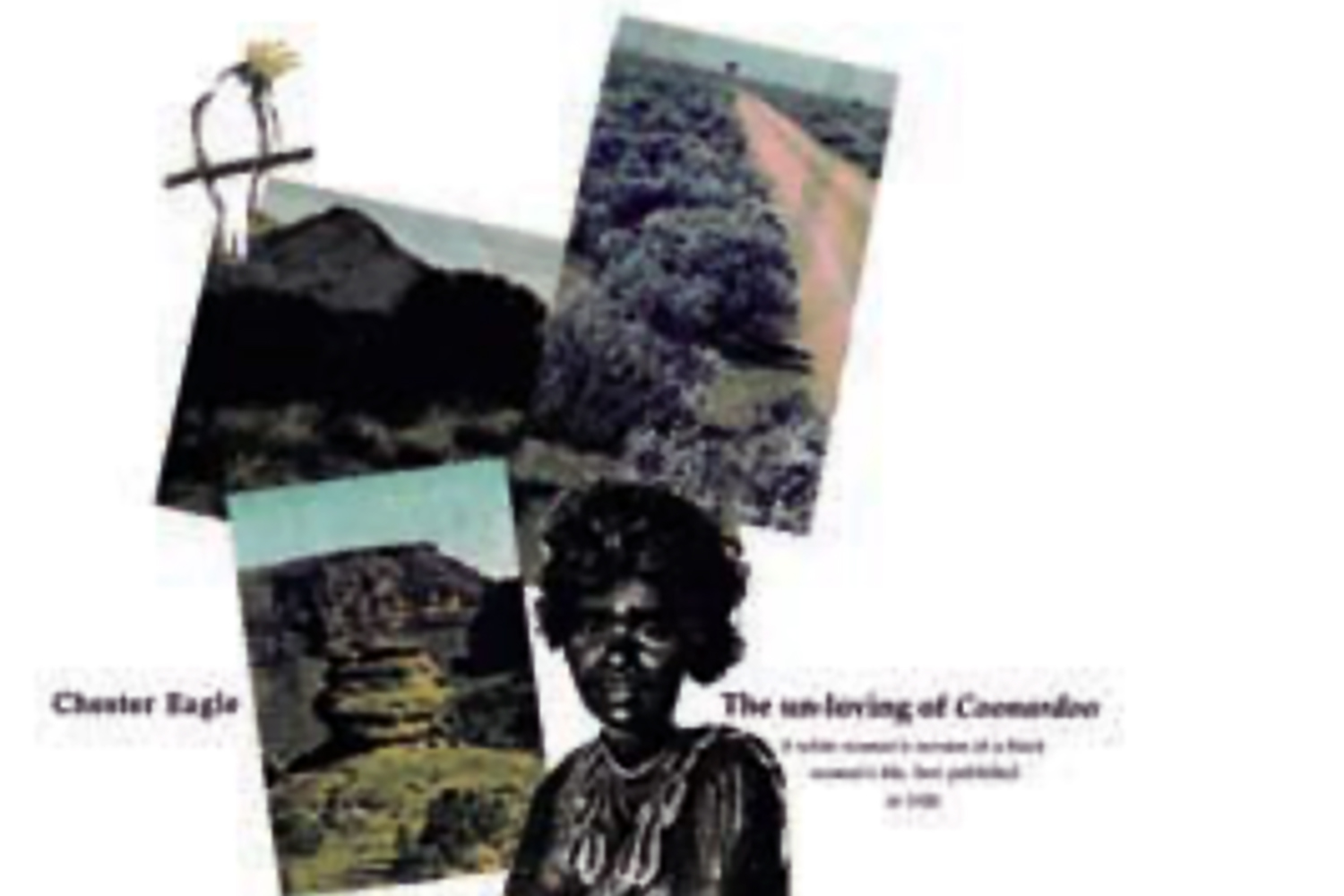

9. The un-loving of Coonardoo

9. The un-loving of Coonardoo

A white woman’s version of a black woman’s life, first published in 1929.

The un-loving of Coonardoo:

What is this book about? It seems obvious. The first word is ‘Coonardoo’, and the last pages show her in the final moments of what has become a wretched existence.

She crooned a moment, and lay back. Her arms and legs, falling apart, looked like those blackened and broken sticks beside the fire.

The book ends, as it begins, on a station property called Wytaliba. It’s in the north west of Western Australia, and the name, according to the Glossary of Native Words, means ‘the fire is all burnt out’. What fire? Wytaliba has been the centre of much activity, and personal dedication, throughout the book. It’s only at the end, when Coonardoo returns to what has been her home, that the desolation of the property, and her own personal desolation, finally overwhelm her. She lies back, her arms and legs falling beside her, and I think it is clear that she, in whitefella terms, is giving up the ghost.

The ghost, from the German word geist, means spirit: the holy spirit. You will notice that even as early as this in my essay about whitefellas and blackfellas living side by side in the Kimberleys, I am using a word, an idea, that is a product of the whitefellas’ minds, not the blacks’. But then, if we go back to that glossary, we are offered jinki for spirit, narlu for evil spirit, and moppin-garra for magician. [read more]

Introduction:

In 1981 Patrick White published an autobiographical book called Flaws in the Glass; the Melbourne Age commissioned two reviews, one of them from Hal Porter, who said, among many things unflattering to ‘Mr White’:

Writers of my sort can be said not so much to read as to examine another writer’s work rather as one car freak examines the vehicle and driving of another car freak. One says, “Splendid vehicle! Superb driving!” Or, “Nice vehicle! Ghastly driving!” Or, “Can’t stand that kind of cumbersomely pretentious vehicle! And what bewildering and erratic driving!”

Hal confesses that the third attitude is his to the novels and plays of ‘Mr White’. I will say no more at this point about Mr White or Mr Porter, but I quote this comparison of writer and car freak because in the essays that follow I am the freak who comments on others of his kind. I know I can’t see my essays as others will see them but I imagine some readers accusing me of many things, and others, well trained, perhaps, in one or another school of literary or social criticism, who will think my observations no more than shallow or ignorant. To such people I can only say that these essays offer whatever it is that a fellow-writer can offer, and don’t pretend to offer anything else.