20. Singing the country: a first look at Carpentaria by Alexis Wright

20. Singing the country: a first look at Carpentaria by Alexis Wright

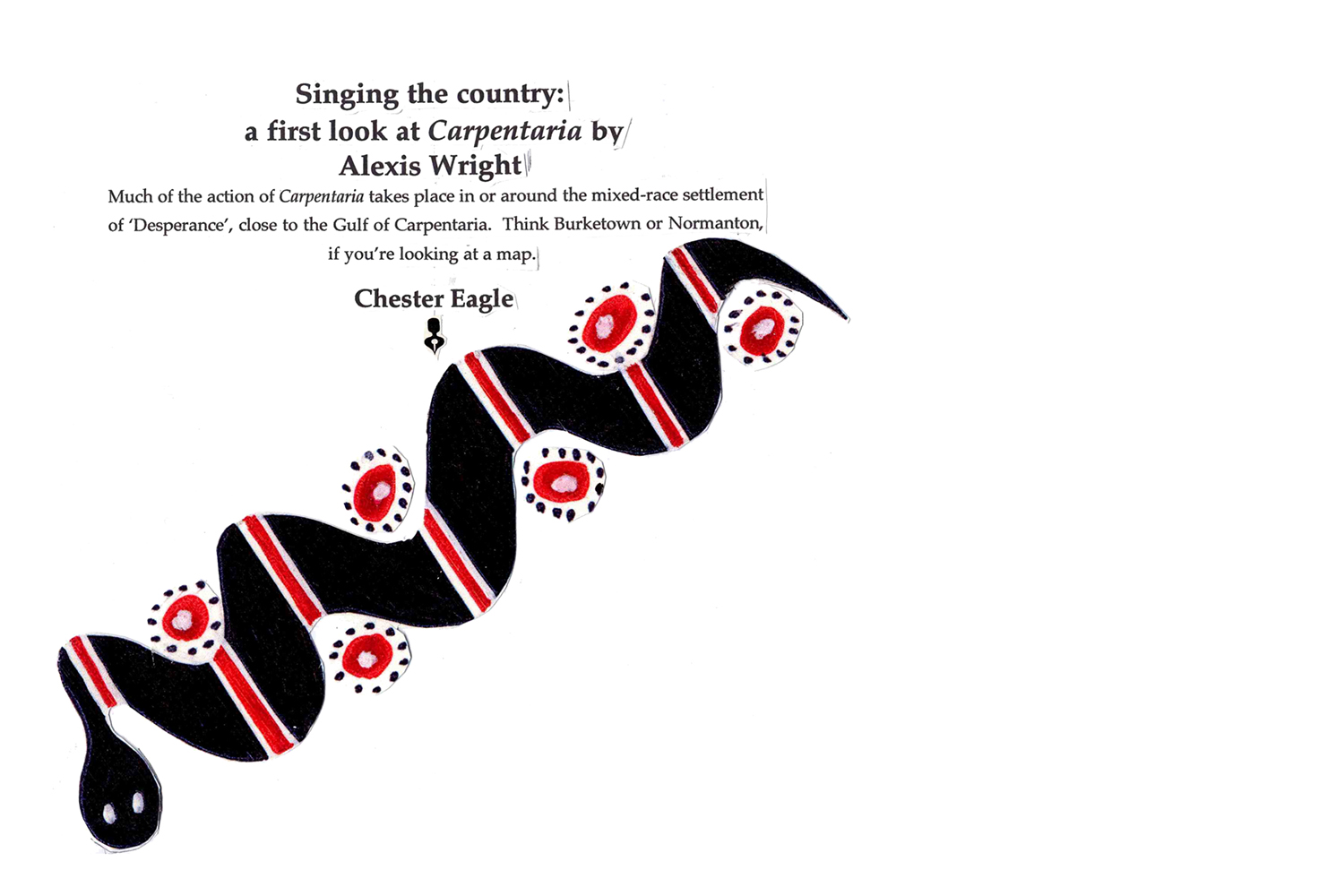

Singing the country: a first look at Carpentaria by Alexis Wright:

Much of the action of Carpentaria takes place in or around the mixed-race settlement of ‘Desperance’, close to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Think Burketown or Normanton, if you’re looking at a map. But be prepared to think big, very big indeed, and in an almost entirely new way, because this is a novel the likes of which we have never seen before. There is a serpent, far underground, who is arguably the book’s foundation, though it has nothing to say. It stretches in a diagonal across the continent, which puts its tail near Esperance on the south coast, at the western edge of the Bight. Australia is built on a mighty scale, and for white Australians, one theme of our history is hope, which, via the language of the French, gave Esperance its name. At the biting end of the serpent, in a remote settlement building its hopes on the prosperity of a company called Gurfurrit (Go-for-it?), white and black miners do the bidding of a New York-based multinational, while other blacks, loathing the operation, and taking up the concept of native title, try to block its progress.

Thus it may seem that the book is about a struggle between the miners and their opponents, the modern world of international capital and an earlier way of life …

… and it is, and yet again it’s not. [read more]

Introduction:

In 1981 Patrick White published an autobiographical book called Flaws in the Glass; the Melbourne Age commissioned two reviews, one of them from Hal Porter, who said, among many things unflattering to ‘Mr White’:

Writers of my sort can be said not so much to read as to examine another writer’s work rather as one car freak examines the vehicle and driving of another car freak. One says, “Splendid vehicle! Superb driving!” Or, “Nice vehicle! Ghastly driving!” Or, “Can’t stand that kind of cumbersomely pretentious vehicle! And what bewildering and erratic driving!”

Hal confesses that the third attitude is his to the novels and plays of ‘Mr White’. I will say no more at this point about Mr White or Mr Porter, but I quote this comparison of writer and car freak because in the essays that follow I am the freak who comments on others of his kind. I know I can’t see my essays as others will see them but I imagine some readers accusing me of many things, and others, well trained, perhaps, in one or another school of literary or social criticism, who will think my observations no more than shallow or ignorant. To such people I can only say that these essays offer whatever it is that a fellow-writer can offer, and don’t pretend to offer anything else.