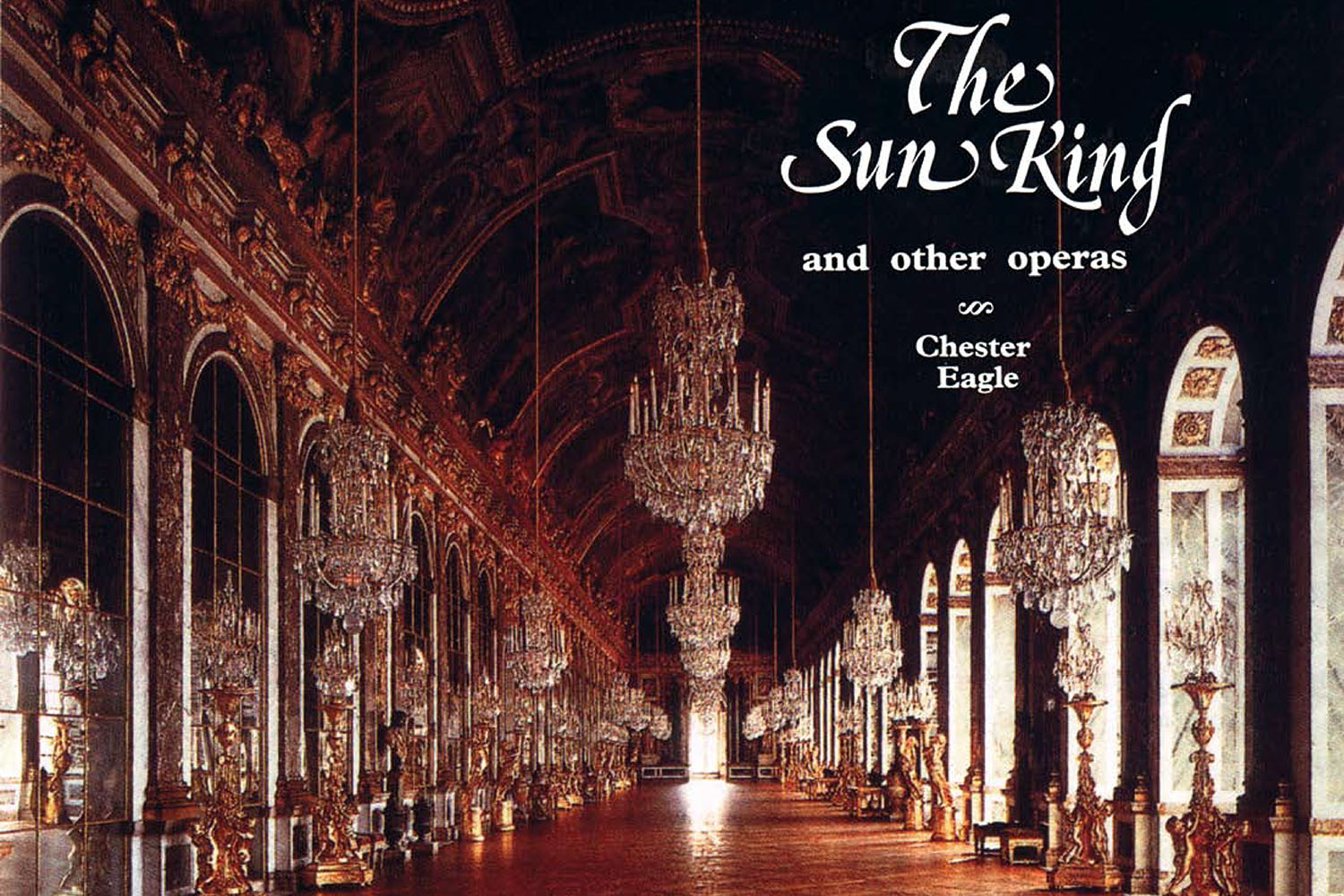

The Sun King and other operas

There’s nothing new to be said about power. Everybody knows everything about it. Yet it surprises us continually. The librettos in this collection remind us, once again, and with a few bites in the backside here and there, of what people – nasties like Stalin, heroes like Beethoven – have done with it. Observers of Australian politics will know what some of these operas are about; in fact, the effect of the collection is to remind us that we are all on stage, day and night, in the crazy opera known as life – or would you prefer that with a capital L?

Written by Chester Eagle

Cover by Vane Lindesay

Layout by Karen Wilson

Circa 54,000 words

Electronic publication by Trojan Press (2007)

The writing of this book:

Late in 2006 I decided that I would write a fourth collection of opera librettos, dealing with the theme of power, mostly, but not exclusively, political power. I drew up a list of possible topics – Ming (Menzies’ supercilious control), Gough (the excitement of 1972), the two faces of Malcolm Fraser (ruthless in 1975 and the noble spokesman who came later), Paul Keating, and the appropriation by John Howard of Pauline Hanson’s vexatious spirit.

As so often happens with my writing, the project had ideas of its own. Power? I began with the clash between Dimitri Shostakovitch and the terrifying leader of his state, Joseph Stalin. There must have been many nights in the life of the composer when he expected that the secret police would have taken him away by morning. Yet, astonishingly, it was the composer who won the battle. His 5th Symphony (‘a Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism’) challenged the dictator head on. Music defeated the murderous men who carried out Stalin’s will, and audiences applauding the work at its Leningrad and Moscow premieres knew very well what they were cheering. Guns and bullets could, if only rarely, be overcome. I put ‘Dimitri’ at the beginning of my collection, and turned to my list of Australian figures.

But no. Next came the absolutism of Louis XIV of France. I’d visited the Chateau of Versailles and its gardens in 1982 and could not fail to observe the absence of the democratic spirit which is so important to me. Versailles is the creation of the Sun King, shining on lesser mortals. Absolute power can rise to great heights. The world needs miracles, and it got one at Versailles. Writing ‘The Sun King’ forced in me a realisation that the principles I espoused had limits, and people with the opposite point of view might be better placed in certain ways.

For the third opera I turned to the memoir of a woman who’d lived in north-central Queensland, an area I’d lately been exploring. She and her husband might have been killed, or forced off their station, by the blacks whom they’d displaced. This frontier battle was fought most tellingly in the hearts of two black women who worked on the station. Maggie and Kitty, members of the local tribe, save the woman they work for, and hence the station which occupies their tribal land. Were they right to do this? It seems they loved Evelyn, their mistress, more than they loved much else which modern apologists would say they should have given their loyalty to. In any case, they made their choice and everything depended on it. Oddly enough, there is, to my mind, almost as much nobility in their decision as in the panegyrics of the preceding opera, where the sun sets on a great king’s reign.

I was by now well and truly in the realm of power. It had a salience which pushed into every corner of my mind. I had for many years admired the cartoons of David Low, the New Zealander who rose to fame in London. He had no way of stopping the events of the Hitler-Mussolini period in Europe, but he could comment, via his cartoons. Cartoons are often described as being funny. This is odd. Great cartoonists have to be apposite in their work; humour can be there, or not, as the cartoonist pleases. Low, I have long felt, was at his greatest when his themes were darkest. Unlike Louis XIV, he was a democrat, at a time when fascist powers were rageing almost unchecked. People in wartime London, and in the worldwide empire of which London was the centre, knew that the expression of their feelings, if it was to happen at all, was most likely to be in a David Low cartoon; this, it seemed to me, was itself the expression of a significant power, even if the powers Low commented on were unimaginably greater. Or were they? Power depends on fear, it is true, but it depends also on the imaginings of those whom the conqueror wishes to control. The mind has to be subdued, and made accepting, every bit as much as the body must be made to tremble. By the time I finished this libretto I was beginning to feel that not only did the project have a mind of its own but that what it was undertaking was right.

I started to relax. The pursuit of power could be farcical. Australian voters have seen two examples in recent years of leadership struggles in which a promise of succession has been broken. In each case, in my view, the body politic, or the public’s faith in it, has suffered a blow more significant than the wounded pride of the pretender. This theme is treated in ‘The PM’s Chair’.

Power need not always be brutal. Coercion can be, and often is, replaced by persuasion and one has only to cast a glance at the advertising industry to see how revolting this can be. Listening to my car radio as I drive around my allegedly democratic city – elected councils, and so on – I notice that the word ‘citizen’, that precious heirloom of good things brought to us by the French revolution – which brought much else besides – is well on the way to being replaced by the newer and nastier ‘consumer’. Hence my title, ‘Aux armes, consumeurs’. I can’t say it more savagely than that!

But there is power in the liberating idea. To my considerable surprise a second composer entered the collection. Beethoven followed Shostakovitch. I was fortunate enough to read a book of recollections of Beethoven by those who had known him, and saw at once the possibilities inherent in the gathering of high-caste Viennese in a square shaded by linden trees. I had the book open as I wrote, but my mind was open to another dimension again. I allowed myself to wonder about the power of the great man’s music, which we today have now had the better part of two centuries to absorb, on the minds of those who knew him. Beethoven, it seemed to me, had, by creating the famous melody of the choral symphony, and the numerous variants and/or precedent versions that occur in a number of his works, given the democratic, humanistic ideal a form which would surely last, as certain political leaders in the following century liked to say, a thousand years!

Hitler and Churchill, the leaders I refer to, make brief appearances in the David Low libretto which has been discussed already.

Perhaps I can end by saying that when I finished the last of my fifteen librettos, I wondered what they amounted to, and realised that the import of a number of them wasn’t clear to me. The librettos about Shostakovitch, Beethoven and Louis XIV are clear enough, because the figures these librettos dealt with are already well understood, but a number of others, particularly the last two, That Beam of Light and The Ship of State, speak in a very personal and recently-invented way about modern democracy and it may be that they embody insights which haven’t yet surfaced in my conscious mind. I rather hope so, because writing is all about giving life to ideas which haven’t yet found their place in the world. I am reminded of Chou En Lai who, when asked whether he thought the French Revolution had been successful, replied, ‘It’s too early to say.’ For years I have been wanting to ask him when we will know and what we will look for in finding an answer. Alas, he is no longer able to reply.

I hope that readers, and in time to come, audiences, will find something to enjoy in this collection.