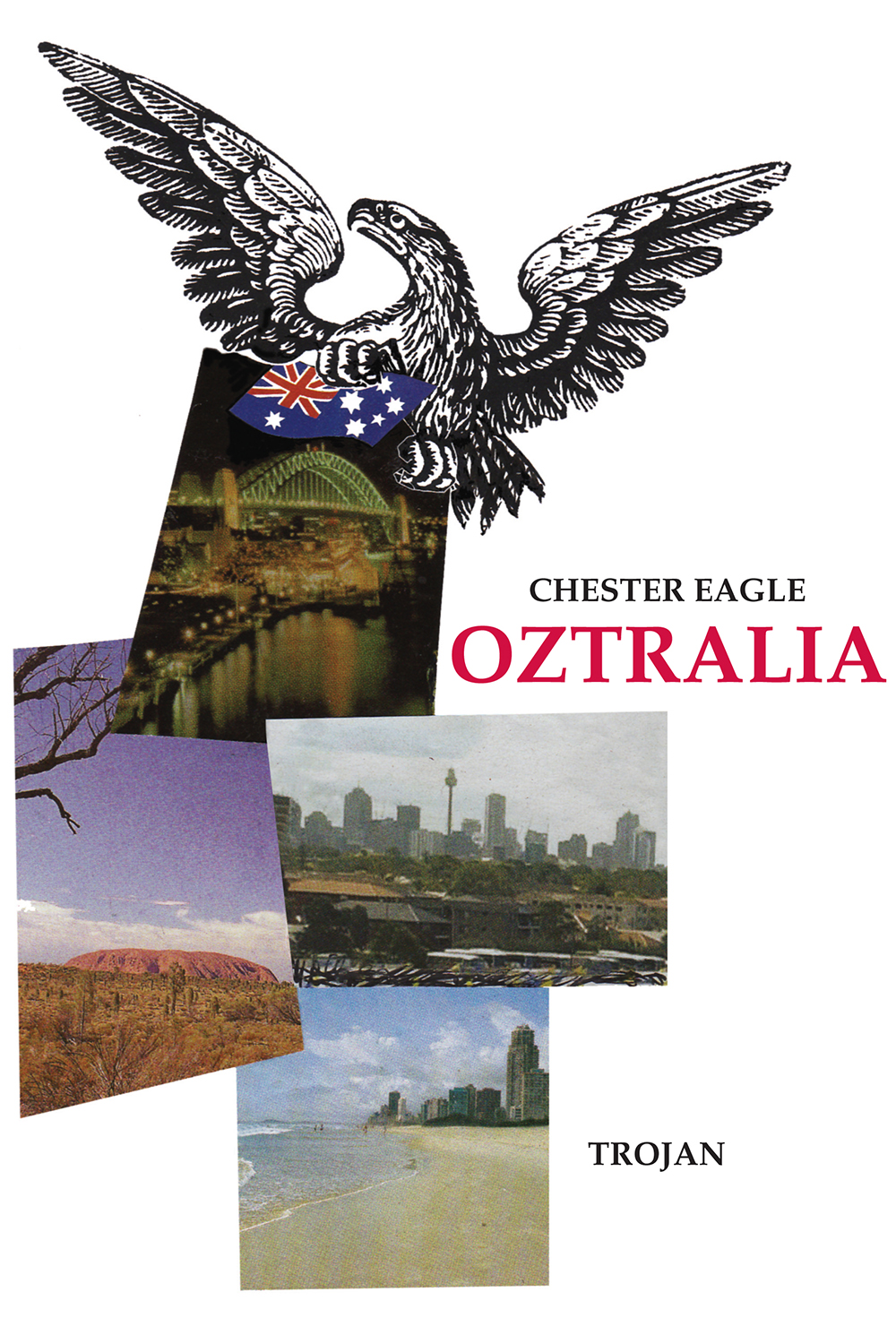

Oztralia

The name of our country derives from the Latin australis meaning ‘southern’ or ‘belonging to the south’; hence Australia, a name conferred by people from the north. The history of this land has been one of allegiance to the British Empire, first, and more recently to America as it’s become the world’s dominant power. Proud as Australians may be of their country, the name it possesses hints at those habits of subservience which are part of its character. There has long been another strand, however, of those wanting their land to be better than its sources, in particular, those expressing the ideas, feelings, intuitions and passionately held values which have arisen here. The essays in this book deal with the Australian land, the responses to it of the black civilisation, the ways of those who came later, but most of all with its writers, giving the land a voice of its own, the sounds of its most deeply felt expression.

Written by Chester Eagle

Designed by Vane Lindesay

Layout by Karen Wilson

First published 2005 by Trojan Press

200 copies printed

Circa 41,700 words

Electronic publication by Trojan Press (2006)

The writing of this book:

When I finished Melba: an Australian city I felt that I would move on to a similar book of essays on Australia. I did. I searched my mind for what I shall call basic feelings about the country and found myself returning to the Bernard O’Dowd poem quoted at the very beginning. This poem posed questions to, at or about the country so it seemed it might be useful to work towards some answers. But how to do it? I found myself differentiating between the land and the life lived on it. This could vary immensely, something we can see easily if we contrast office workers in city towers with the lives of semi-nomadic tribal people living off the land.

The black people lived very close to the land and its ways, but it seemed to me that white people did too, even though they appeared frequently to ignore it. The land influences us, and its effects can go much further; I had myself been brought up as part of a farming family and from my experience white people who worked the land became deeply attached to it. As a young man I thought the landscape was boring and as I grew up on the flat plains of inland New South Wales it wasn’t hard to justify this. It was harder to sustain, though, when I too came to love the land. Eventually I wrote about it (Mapping the paddocks), and then I read Joan Austin Palmer’s Memories of a Riverina Childhood (1993). Joan was sixteen years older than me, and her family’s properties larger than my parents’ holding, but there was a great deal in common. Reading her book made me think of all the station properties I’d been driven past in my childhood. I saw that even though I was as tied up in the global financial system as anyone else, the connection I felt with the land would not be denied. This, then, was the way I would approach writing about Australia.

Which I called Oztralia, for reasons made clear in the introduction. It wasn’t long before I was riffling through Miles Franklin’s All that swagger, a book I had come to love quite a few years earlier. I had driven through Talbingo before I became aware of the Franklin family’s attachment to the place, and I had loved it at first sight: it was the most beautiful place I’d seen. Years passed before I discovered the Franklin connection with the place, but when I discovered it I felt a bond with Miles. No wonder it was so important to her.

Another important influence in the development of this book was a visit I made to Central Australia with my daughter and friends; on a sign near one of the waterholes in the West Macdonnell ranges I read that these mountains had once been as high as today’s Himalayas, but had been eroded over time. Time! The aboriginal people had known the land through many thousands of years, had seen climate changes, and had adapted to them. The land presented itself to my thinking as a fundamental force in our existence. It seemed to me that Australian life had been exposed to many influences external to that fundamental shaping force of the land (the British empire, the American empire), and that the interaction of these external forces with what was local and undeniable was where the action was, so to speak, in the shaping of my country’s civilisation. British, European, even American ideas weren’t quite the same when moved to the context of the land we lived in and on.

My approach was settled; I had only to write. There are only two more things I want to say about this book, and they are connected. I had had for many years a little collection of writings in which various of my fellow authors described the business of folding sheets, or perhaps a tablecloth. Hal Porter was the first writer I remember doing this and I’d read his account with delight because I’d seen my mother and numerous other women doing the same thing. It had been one of the rituals of my childhood. Hal described it and so did others. For years I wanted to do something with these writings but all my ideas involved developing the idea in some way whereas I thought the quotations should stand without explication. Finally, in this book, I got my chance to put them on show in the simple way I thought was right.

In the book’s last essay I do a similar thing with writers summoning up in some way the idea of Australia, or the way Australians lived. I managed this process as carefully as I could but it took control. I had heaps of books on my oval dining table, sometimes two, three or four books by the same author. I browsed through these books that I knew well anyway, and put slips of paper in to mark possible quotes. I stared at the growing piles of books and told myself that many of them would have to go back on the shelves because the piles were too big. I added more. Then, when I began the essay, the whole thing became easy. As I started writing each day, I picked up a couple of books, riffled through them speedily for a quote that suited, and put it in my essay. (Mine?) At the end of the writing session the book went back to the shelves. Any number of wonderful and much-loved books didn’t get quoted but the essay was writing itself. The process was in control, as happily as ever. I read the essay now and see that it knew what it wanted, and had used me to get what it needed. I am privileged to be a writer. I serve a demanding but wonderful master.