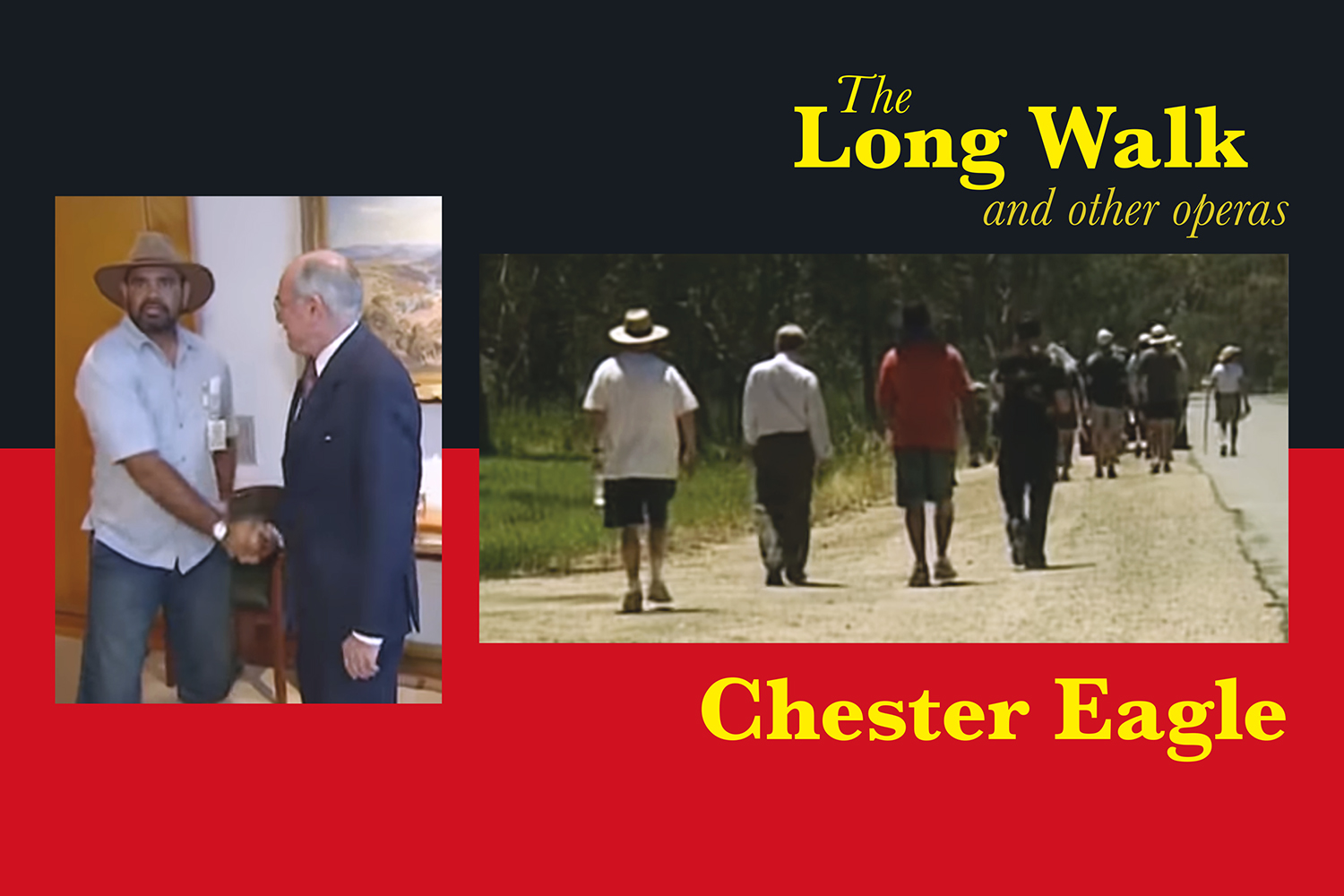

The Long Walk and other operas

My first collection of opera librettos was published in 2003; this is the seventh. First of the new librettos to be written was The Long Walk, but I have placed it last because for some reason I see it as summative of the other, later, librettos. I think of my librettos – over a hundred by now – as resembling political cartoons, in that they concern themselves with social comment of some sort rather than vehicles for powerful passions in the manner of Verdi or Puccini. If they have a starting point in the world of European opera it would have to be Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, an opera without arias and with an unusual way of combining words and music. Most of the librettos presented here incorporate a scene, or at least a fragment of some well-known piece of European music, operatic or otherwise.

Written by Chester Eagle

Designed by Chester Eagle

Layout by Karen Wilson

Circa 28,850 words

Electronic publication by Trojan Press (2021)

Twelve opera librettos, with introduction and production notes.

The writing of this book:

My first collection of opera librettos was published in 2003; this is the seventh. First of the new librettos to be written was The Long Walk, but I have placed it last because for some reason I see it as summative of the other, later, librettos. I think of my librettos – over a hundred by now – as resembling political cartoons, in that they concern themselves with social comment of some sort rather than vehicles for powerful passions in the manner of Verdi or Puccini. If they have a starting point in the world of European opera it would have to be Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, an opera without arias and with an unusual way of combining words and music. Most of the librettos presented here incorporate a scene, or at least a fragment of some well-known piece of European music, operatic or otherwise.

We may say, therefore, that the underlying reason for the existence of this compilation is to draw attention to the contrasting contents of Australian minds. European practice controls our aesthetics, while aboriginal voices insist on retaining a significant place in our modes of thought and behaviour. The two will draw closer over time, though I, alas, will not be around to see what the combination will be like when, eventually, it exists. The best I can do, in the present, is to offer these new, combinative librettos with a few remarks by way of explanation.

We begin with Opus 131, a reference to the late music of Beethoven, and more specifically my request to my father, visiting New York in 1955, to bring me back a recent recording of the string quartets of Beethoven. He went to the famous store of Macy’s, they didn’t have them, but said they would get them in for him. They did. Thirty-nine years later, I visited Macy’s myself, and used the same quaint, wooden escalators Father must have used on his son’s errand. Father had no interest in music but he enjoyed his visits to Macy’s, procuring something special for his son. In my libretto, Beethoven’s music has something much more meaningful to offer a dying man than the time worn recipes of the church.

The second libretto, Zum letzten Mal looks at the idea of a god- king, or king-god, and the necessity or otherwise for the human mind to create such a being. Richard Wagner most memorably explored this combination of godly and human characteristics in Act 3 of Die Walkure, and I have borrowed a little of his finest music by way of illustrating my theme.

My third libretto, Statua gentilissima, again combines the supernatural – the Commendatore’s statue from Mozart’s Don Giovanni – with something keenly felt in my own world. A recent university newsletter made me aware of the deaths of no less than eight of my college contemporaries, among them one I’d been close to when we were schoolboys together. He was dead. His son said he had died with the music of Mozart in the background. I was disturbed by this. A part of me had died with him. I had a libretto to write.

Still in this mood of being absorbed by the divine and what ideas of this sort can offer human beings, I turned to Bruckner’s 8th symphony – the end of the slow movement. I contrasted this with the death of a load of passengers whose Malaysian Airline plane disappeared mysteriously into the Indian Ocean, far from its destination in Beijing. Bruckner’s music tells a different story from that offered by scraps of aeroplane washed up on island beaches of the ocean it plunged into.

I placed Recovery next. The central figure is concerned with money as power but is compelled into understanding that his way of life is abominable in the eyes of the women he’s been attracted to. It’s perhaps the screaming of his teenage daughter which finally forces him to see what his women have been telling him. He believes he can redress the faults they see in him. This is doubtful but the libretto gives him an interim benefit of the doubt. The action ends with his recovery still at least a possibility. Was I being too charitable? We must wait and see.

Destiny, placed next, was written last. The European music here is by Claude Debussy, whose only completed opera is the point of origin for many of my librettos. Debussy’s King Arkel sees the events of the opera as destiny; I’ve taken that to mean, simply, that which happens. In the Australian part of the story, quite a lot happens, but the official, or accepted, aspects of the story don’t by any means coincide with what happened at the front line. This is only resolved when Haydon, the brother who returns alive from war, accepts what’s happened to him and his brother as the basis from which he must go on. He is greatly helped in this recovery by Marion, who, in need of help herself, urges Haydon to sing! He does, and this marks a new start in his otherwise crippled life. Max, his brother, has long been dead.

Faith comes next. Faith is represented by the music of Heinrich Schutz, an exponent of Christianity as commanding and authoritative as was J S Bach, a hundred years later. Faiths, it appears, are only tenable, sustainable, when the period upholds them. An Air New Zealand crash in Antartica releases a flood of pain and passion which makes Schutz’s faith unsustainable. The plane was doomed from the moment it took off.

Our other selves examines marriage, from the viewpoint of people affected by the counter-culture of the 1960s and ’70s, and from an older, earlier, more traditional view of marriage as both binding and sacrosanct. The libretto offers a choice but makes it clear that the choice having been made, its consequences have to be accepted.

Notre exil mortel was the first written of the librettos combining a European and a contemporary Australian theme. It uses a few minutes of superbly concentrated music by Hector Berlioz to push, indeed compel, a young medical student to make decisions about how she will live now that she’s become pregnant to a man she has no wish to marry – and yet he will be the father of the child she decides to have. Her position is difficult but the music clarifies her situation for her.

To Mozart again, to hear him laughing, and then we return to our aboriginal theme for the last two librettos – The gates of death and The Long Walk. The first of these shows the position, and perhaps the acceptance, of aborigines in my Gippsland years (1956 – 67), while the final libretto – the first written – picks up the same theme at the time when Michael Long, formerly a champion footballer, decided that the position of his people needed improving. His walk became famous, but I hope that you will notice that the libretto shows the aboriginal issue is still largely in the hands of white politicians and media people.

There are unexpected twists and turns in these librettos, bringing them, I hope, to represent contemporary realities for all that they acknowledge earlier European constructions of our civilisation’s ways of doing, seeing, understanding things.