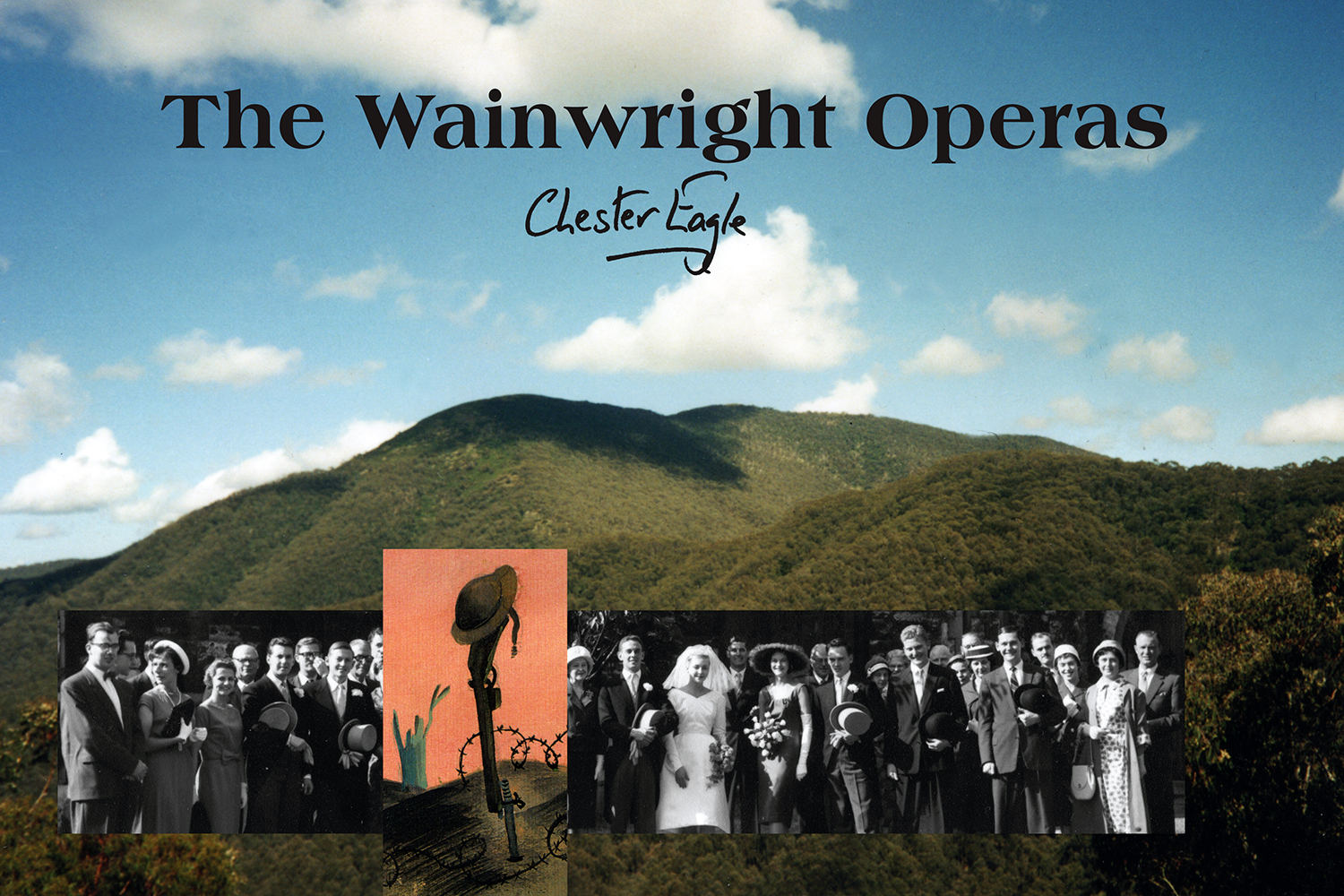

The Wainwright Operas

In 1997 Trojan Press published Chester Eagle’s novel, Wainwrights’ Mountain. Offered here is a conversion of that book into a sequence of fourteen opera librettos, which, for the most part, stay close to the events and motivations of the novel from which they derive. There are differences of course, dictated by the new form of presentation. Everybody sings! The lordly Giles looks down from his mountain, cruelly indifferent to his sons, who turn into the agents of frustration and revenge when, first, they kill their father, and then go off to a war which suits their natures uncommonly well, before returning to burn the tree house where they grew up. Lucy, the eldest surviving daughter of Giles and Annie Wainwright, carries the burden of everything her parents couldn’t achieve. After years of loneliness she finds a husband and the two of them soar to the operas’ greatest heights, in the mountains where their stories belong. In another sequence, there are families from Melbourne whose lives present an even greater variety of fates and passions. The novel was always wild in its imaginative life, and here it sits today, waiting for the music which will bring it to life in a new way.

Written by Chester Eagle

Designed by Vane Lindesay

Layout by Karen Wilson

First published 2005 by Trojan Press

Printed 124 copies

Circa 105,500 words

Electronic publication by Trojan Press (2006)

Fourteen opera librettos, with introduction and production notes.

The writing of this book:

This project sounds simple: I converted a novel into a sequence of fourteen librettos. I gave myself a requirement at the outset that each of the operas should to be able to stand on its own, while also forming part of a sequence that could be presented as such. Again this sounds easy, and as I drew near the end of the project I was telling friends confidently that it had been an easy process. It is only now, looking back at the notes I made in the early stages, that I see how much care I had to take to achieve these aims.

I began with the fourteen chapters of Wainwrights’ Mountain, and summarised them with some care. As with didgeridoo, I edged my way forward, making any moves that seemed clear, leaving alone anything that wasn’t obvious. I have great faith that things will work themselves out if you let them have the space and time they need to do so. Once I had my summary of the novel’s chapters I began to look for things that the novel presented as ‘scenes’; I was also looking for beginnings and endings. The novel tells its many tales by way of following two family lines. In the novel I use a variety of tricks and devices to interweave these stories, bringing them ever closer until, at the very end, they are brought together by such outrageous trickery (metaphoric nonsense, I would call it, if asked to define) that normal ideas of how the world works have to be suspended. This may work in a novel but the stage, though it has many forms of magic, couldn’t allow that one, so I knew that the ending of the sequence would cause me to rethink. In the meantime, I would do whatever seemed easy and postpone decisions about things that puzzled me.

After a time I began to pull apart the sequence of events in the novel and rearrange them so that they began to link with theatrical logic rather than on-the-page narrative logic. It was a matter of respecting the way the novel had worked while slowly stretching and pulling it into new shapes. This was helped by the fact that I had always felt that the novel would provide film makers, should they be interested, with the source for some excellent film scripts. The film scripts began to turn into librettos; I felt sure it could be done, but it had to be done slowly and respectfully.

After a time I did away with the chapter numbers and headings (‘In which …’) that I’d used for the novel. The headings became ‘Opera 1, The tree house’, Opera 2, ‘War’, and so on. I had fifteen such headings. Thirteen of them held, but I merged the last two, giving me fourteen. This was the same number as there were chapters in the novel, and this, arbitrary as it is, seemed ‘right’. So then I took all the notes and ideas I had and pushed them under one of the fourteen opera titles. What would fit where? It soon became clear that the operas wouldn’t fall into conventional acts. Each would be a succession of scenes, and the last scene would bring the opera to its conclusion, even though an earlier scene might present the opera’s heart. I think there are a number of examples of this in the sequence of fourteen.

When it all had a reasonable promise of falling into place, I started. I began writing the librettos on January 2, 2004, and, to make sure that no stylistic discrepancies crept in between the telling of the two stories, I wrote Opera 1, The tree house, concurrently with Opera 2, War. Opera 1 only took a few days and thereafter I simply wrote the operas in sequence, finishing Opera 14, Cloud, on August 20, 2004. It had been easy, I told my friends, but only because I’d been careful when taking all the early, decisive, steps.