Emily at Preston

Written by Chester Eagle

Design by Chester Eagle

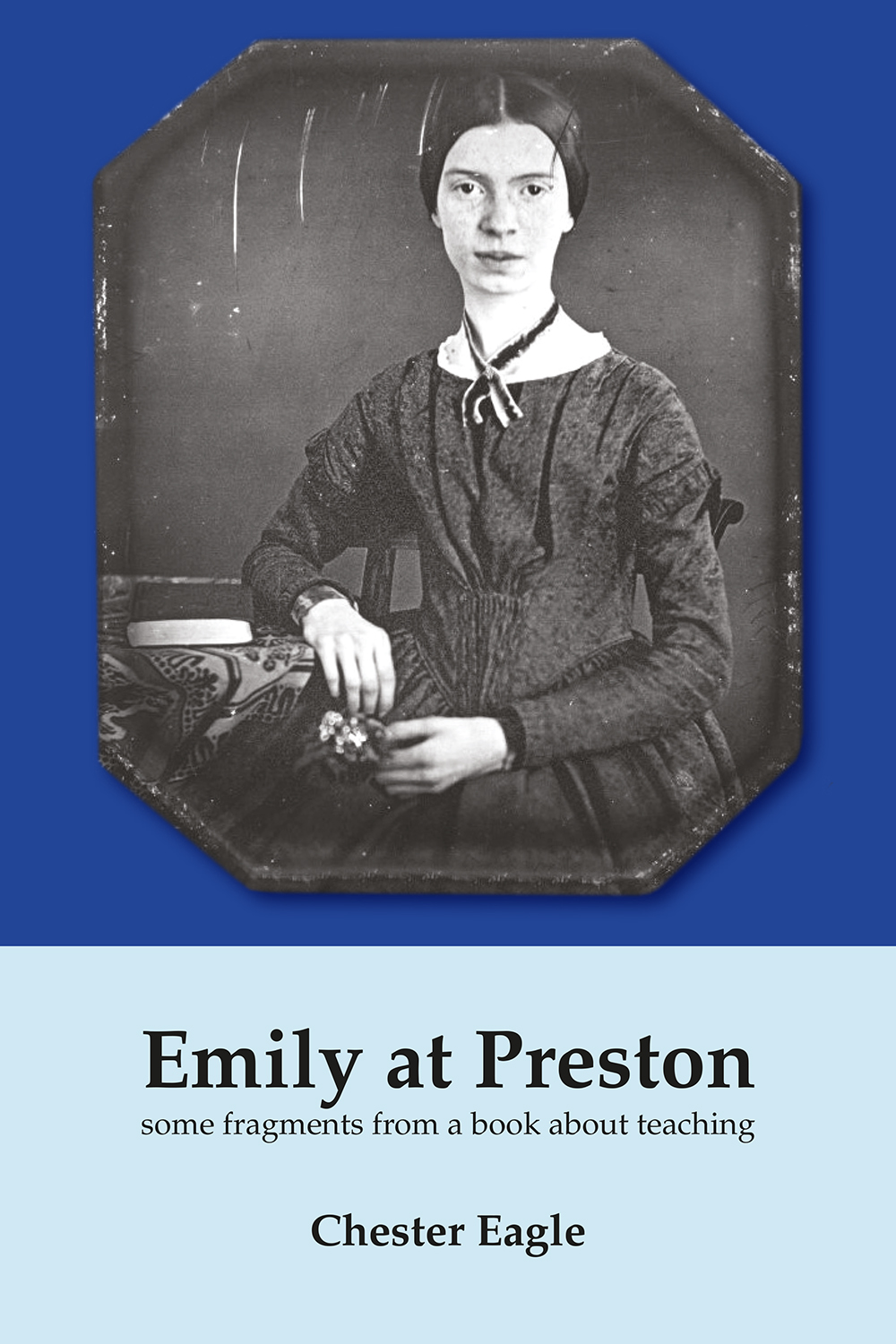

Image of Emily Dickinson from Wikipedia

Layout by Karen Wilson

200 print copies by Design To Print

Circa 6,400 words

Electronic publication by Trojan Press (2015)

Selection of extracts from All the Way to Z (2009)

Emily at Preston:

The passages that follow are taken from the memoir/essay All the Way to Z, available in its entirety on the trojanpress.com.au website. It’s a book which deals with my experiences over thirty years in education. For this selection I’ve chosen passages dealing with some of the highs, lows and oddities of my later years at what was then called Preston TAFE College (there have been at least two name changes since). Some minor editing has been done to fit the passages together in this sequence.

Preston

I had long been an admirer of George Orwell. I went searching through his books for passages I wanted my students to consider, then I had them printed with the punctuation removed. Words, words, words. I passed these pages around to my students, and told them to watch – ‘read’ – carefully while I read the same passage to them from the printed book. I read each passage slowly, emphasizing the shape of the sentences, as indicated by Orwell’s punctuation. Then I put the book down, and took up the sheet I’d given the students. ‘Get the sentences first,’ I told them. ‘Put in the full stops, then punctuate each sentence in the way that makes it easiest to follow. To understand.’ They’d work on it and so would I. After a time I’d put my own exercise in front of me and take up the printed book again, and tell them how Orwell, generally regarded as a master with the language, had punctuated for himself. The students often did quite well, but just as often they were all over the place. The amusing thing, for them and for me, was that I, despite my familiarity with the originals, could never punctuate in quite the way that Orwell did. ‘Punctuation,’ I used to tell them, ‘is not entirely a matter of right and wrong. There’s a personal element in it.’ I suppose I had to say that, since I couldn’t get my Orwell right, but the students didn’t seem to expect perfection from me, which was just as well, since there were places where I couldn’t really tell why Orwell had punctuated as he had … but there it was, his marks were as they were; at about the same time I bought for my son an edition of 1984 in a photocopy of Orwell’s manuscript, with alterations and revisions in his own hand. It was the sort of thing I’d like my students to have had, but was far too expensive for them to buy, or the college to buy, for that matter. I’d love to have had a vast store of resources for the study of writing but, like all my colleagues, I made do with photocopies of things taken from books, magazines, even the morning’s paper. We developed a very contemporary frame of reference for the teaching of our TAFE programs and I think that was a virtue in the students’ minds.

Why? The question makes me think about the students I encountered in Preston over twenty years. Preston students didn’t want to be where they were. They were ready to move if they could. Some of them had backgrounds that limited them, and they knew it. Others were comfortable enough but they had nothing behind them, pushing, or drawing them forward as if that was their natural direction. Such tradition as the area possessed was like a weight around the legs, dragging people back, or down. If you named Preston or any of the suburbs around it as where you came from, nobody would be impressed. No store of respect or goodwill had ever been built to support the place. I began to take my students on walking tours of places it might help them to understand. We began with Collingwood, because it was near, and because it had lifted itself out of being a slum, via the possession of a famous football team. Collingwood existed on flattish land near the Yarra, and it was overlooked by the nearby hill of Kew, where the Roman Catholic Archbishop lived in ‘Raheen’. Frank Hardy had written his famous ‘Power Without Glory’ about a son of Collingwood, John Wren, who’d fought his way up, via crime and thuggery, to a home not far from the Archbishop’s: the two of them, in that mysterious world of Catholics, found an alliance of some sort.

Yet Collingwood had changed, and I wanted my students to see what was new, and what remained. We caught a train, and we walked about for a couple of hours. They could see how tiny the holdings were; Preston was superior in that. They could see renovations, and attics being built to give an extra room or two. They could see remnants of old-fashioned working class respectability, like brightly polished brass names of houses, or knockers on front doors; and they could see that newcomers obeyed another set of aesthetic commands, mostly issued by hardware stores via TV ads. There were cars crowding the streets as affluence pushed its way into the lanes where floodwaters had once taken days to drain away. The people who play football for Collingwood now, I told my students, don’t come from the area any more. The days when the black and white teams were feared because they played with a frenzied belief in themselves as the only thing keeping despair at bay were far behind. Collingwood had changed from a social reality to an idea. The name no longer referred simply to a place but a construct of the culture; Collingwood was something they carried around in their heads. They could see this because their own suburb, a little way to the north, had absorbed this unconsciously, knowing without realising, if I may put it that way.

Then I took them to East Melbourne, a little further down the line. Again, the blocks were small, but not so tiny, and the homes, many of them well-preserved, belonged to people who had pride in themselves. There were a few big blocks with grander homes than Collingwood could display, and my students could see that although East Melbourne was a much nicer place than Collingwood, it had taken shape in the same period. The ideas, the forces of a period, I told my students, manifest themselves in many forms and many directions: to know a period or an historical movement, we have first to gather together and then to reconcile those different manifestations, and at the same time we have to recognize new forces breaking in. I showed them a spot in a corner of a park where I had heard Arthur Calwell, later Leader of the Opposition, giving a speech. This was before television, I explained, as if I belonged to a world so strange that I could have told them anything. They liked East Melbourne, but when I took them through Toorak, they were resistant. Stiff. Impressed, but unwilling to say so. I pointed out that wealthy people encouraged trees, and allowed them to grow. My point about Preston was obvious. The huge trees of Toorak would never have been planted, would have been lopped if they had been planted, and would have been taken out by Council or by neighbourly disputation if they’d ever grown as big as they were allowed to do in Toorak. ‘Look at Heyington Station,’ I told my students, pointing it out: ‘See how discreetly it’s tucked away? Compare that with Saint Georges Road. People shape the world around them in accordance with their ideas of themselves. The confident make a strong, confident world …’

That was a sentence I let my students finish for themselves. They knew very well where that sort of thought would lead. By now I’d begun to like my students sufficiently to take their side. I realised this at an unusual place. Bell Street, one of the city’s traffic rivers, joins hilly Heidelberg in the east with Preston, then goes on a couple of suburbs further till it runs into the stretches of the city reaching north-west. I drove to work along Bell Street and home again. It became a habit of mine to fill up with petrol at a tyre depot where I was served, as often as not, by a powerfully built young man who struck me as having a strong mind, but a truncated education. He was curious about me, and asked me questions. I answered him freely, always. He said little in return, but I knew he was listening. I felt I represented for him one of those outsiders who think they know. Confident bastards whom the locals can never find a way to pull down, thus proving, all over again, that it was outsiders who had their hands on the levers of control while locals could do little but obey. Resentment ran deep in this strongly built man but he was too wary to let it show. He told me one day that he fancied the idea of moving to the eastern suburbs. He’d been out there lately, and they had it better than he did, here. I told him I was happy to live in the north of Melbourne, and that the eastern suburbs lacked a lot of the spirit that was strong, if suppressed, where he lived and I worked. By then our tertiary orientation programs were highly sought-after, so I could afford to be a little smug. He filled my tank, hung up the hose, then screwed the cap back on, doing these things deliberately, as if they were part of the statement he was going to make. I gave him my twenty dollars, and he stood with the note in his hand, staring across the traffic. ‘All the same, I reckon that’d be a good place to live.’

He meant anything would be better than Preston. He wanted out. I knew that we’d reached the end of one of our conversational strands. Getting out was what Preston people wanted. There were no worthwhile ladders in their suburb, no rungs to climb, one by one. You couldn’t get anywhere, you couldn’t succeed at anything worthwhile. I couldn’t argue. I got in every day, and out again; that was why I was stopping where this man worked. The car that brought me to him and took me away again was a proof, a basis, underlying what he saw as the betterment of getting out. It seemed to me that even if he moved to an eastern suburb he’d be working in a garage or something of the sort, so he’d be no better off, but he, I knew, saw it differently. If he got out, he’d have got out! He’d have a chance, whatever the chances were in the place where he’d arrived. The programs I was in charge of at the college, preparing people for tertiary study, were successful because of this urge to get out, to make something of themselves, which was in our students every bit as much as in the man who served me petrol. I’m sure, also, that he would have thought he was more honest, because more realistic, than I was. Preston people knew that other places were better. I would have answered that what mattered was not the place, so much, as the level on which a person operated in the broader society, but my petrol man, watching Bell Street passing him every hour of his working life, wouldn’t let himself be distracted by irrelevancies like that. Everyone in Preston was on a lower level, even if they deceived themselves into thinking they weren’t. I decided, after a time, that my petrol man was right. He’d intuitively expressed the classic problem of the refugee – I’m in a place I don’t like, I want to get somewhere better. Counter-argument: shouldn’t you stay where you are and make it better for everyone? Answer: Stuff everyone, I want to be somewhere better. Counter-argument: That means the bad places get worse and the better ones get overloaded with people pushing to get in: what’s the good of that? Answer: I’ve only got one life and I want it to be better than it is. Out of my way!

When I’d first gone to Preston I’d observed that it wasn’t a badly built suburb. If only it had more trees! Gardens! Trees and gardens, I’d come to realise, are the products of hope. If people are happy where they are, they’ll make things flourish. They’ll build on the buildings and change the quality of the air, the atmosphere, around them. Gardens link; they draw people outdoors, they invite people to step into the world around them, leaving their personal concerns, such as they may be, inside, locked away for a time. Streams of traffic like Bell Street are not part of this. They’re mobility, whereas gardens are places of rest, repose, creation … and Preston had very few gardens of note. This inability, deficiency, was at the heart of its psyche, and the young man who served me petrol, and listened to me, grudgingly, answering his grumbles, felt his years were slipping away and life’s chances, its possibilities, were vanishing.

Students

In later years, I was teaching a group about Australia’s electoral system. I had maps of each state showing the boundaries of electorates. I’d read up on voting systems. I spread these maps on the table and invited my students to analyse the workings of our parliamentary system from the ground up, as it were. The keenest, and sharpest, mind in my group was Domenica’s, a beautiful young woman from an Italian family. She sensed where I was going to take a discussion and got there before me. I began to wonder how far her mind would take her. In the same group was a young man I wanted to call Ray; he called himself Raymond. He was slim, good-looking and – fateful attribute – knew it. One Monday morning, Domenica was absent. I took little notice. Then I didn’t see her for three weeks, and when she returned, she was different, or should I say indifferent. Something had happened. Raymond began to stay away too. We were fairly casual about people dropping out at that time: an urgency about attendance came later. From a few inquiries and remarks I heard the students making to each other I learned that there had been a party at Raymond’s house when his parents were away, that Domenica had been there, that she’d slept with Raymond and, oh dear oh dear, had fallen in love. ‘Fallen’ is a strange word to be attached to love as if it is its natural clothing; ‘fell pregnant’ is even worse. Domenica wanted the love she felt for Ray(mond) to be a source for their two lives, or so I interpreted things, and he was no more than preening himself for having a beautiful woman under his influence. Domenica didn’t finish the year; I no longer remember whether Ray(mond) did or not. I finished my teaching of the electoral system and went on to something else. I’ve already said of a number of my students ‘I never saw him/her again’ and that, I’m sorry to say, has to be said of Domenica too.

Years passed, as they have a way of doing, and a young woman called Nadine was in one of my classes. She was a year or two older than the other students, took up ideas easily, and used them fluently; it was a pleasure to have her sitting at the other end of the tables, an influence on her fellow students almost as strong as my own. Everything she did was handed in on time, easily and almost unnaturally well: I remember, though, a morning when she wasn’t in her place. I started the class, and perhaps ten minutes after we’d begun, Nadine came into the room, carrying her things, saying, ‘Sorry I’m late.’ I looked up and saw tears in her eyes. It was a long time before she joined the discussion, but when she did, she was as clear as ever. For the time being, at least, she’d overcome whatever had happened to distress her.

Nadine went to Latrobe University. A couple of years later, I was sitting in my office of the time, directly above the humanities office in the former trade sector, when Joy, the humanities secretary, rang to say that a visitor was coming up to see me. ‘I won’t tell you who it is,’ Joy said, teasing. In walked Nadine, beautiful as ever, and radiantly confident. She needed a brief note certifying something or other for somebody at Latrobe. I did this for her; she told me about the courses she was studying, and the ones she’d completed, then we went down to give Joy the letter I’d written, and then, as happens all too often in these pages, and in a teacher’s life, Nadine left. Joy was the wife of a banker, and she’d learned from watching her husband’s work and the people it involved, that people build on their hopes and that there are as many failures as successes. Preparing the letter for Nadine, and then sending it to her, would only take a moment, but I felt that the job was as special for Joy as it was for me. I sensed that Joy knew how much success meant to Nadine, and also that our former student wanted me to know how well she was doing: it was a mark of respect, and of something else very special – not love, but openness – which she felt for me and knew was available for her.

Tom Reid. I realise, in mentioning his name, that the students who’ve mattered most to me have all had an intuitive realisation of what they were supposed to be receiving; in a sense, they knew what was coming before it was given. Tom was such a student. When he handed in written work one had only to glance to know that he’d grasped all he’d been supposed to grasp, and he’d perceived, also, where these ideas led. Teaching is easy with students of this sort. It gives a teacher confidence to know that for someone else in the room it’s easy too. The mind of the teacher stretches, gainfully, in hopes of being able to do a little more. Oddly, the presence of those who grasp ideas quickly helps the teacher to be patient with those who are slower, or even backward. One is good-humoured because one knows that there is already success in the room, and someone else, the quick and able student, who is being patient. If learning comes easily, it’s flattering to both student and teacher, and it’s helpful. It seems to stimulate the creation of patience with those who are finding it harder. The whole thing, if it’s easy for some, becomes an amusing game, and one feels, as a player who already knows that s/he’s successful, that a good outcome can be achieved eventually, one way or another, and it will be easier if we all have a laugh at the difficulties – even those who are stumbling over them.

Tom did well with us, and left. Latrobe again, as I recall. I saw him at a party one night, in the flat of some very young teachers, not in my department I’m relieved to say, where there were a number of ex-students present. It was all a little too close for comfort, and I left early, but not before I saw Tom sitting on the stairs outside a bedroom with closed door, pulling on his shoes. I felt that his pants hadn’t been on very long, after being off. Then I was distracted by a colleague who told me that the man she’d loved had been married that day to someone else. I held her for a while, then slipped away. Weeks passed, then the grapevine told me that Tom had become a convert to the pseudo-science/religion of scientology which was festering in our city at the time. I was appalled. That clear, responsive mind …

I never saw Tom again.

Nola

The internal dynamics of a group are unpredictable, but important for the quality of teaching. I had an art class for English and a young man called Eddy looked to be the heart of the group. He was small, quick, and set the pace for the others. I had high hopes of what we would achieve when we got onto the novels we were going to study. Then something happened to him, and he lost interest. His essays grew shorter and they said nothing. He was polite, but withdrawn. He wasn’t doing enough work to pass the subject and I gave up on him.

Then a girl called Nola became interested. She read the novels I told them we’d be working on and asked questions that showed how far her mind had already advanced. She moved around the table from her habitual place and sat beside me, on my right. Her friend Sophie, Greek like Nola, responded by becoming much more vocal in class, though this was of doubtful benefit because Sophie was the sort of person who needed to be central, via drama rather than by thoughtful contribution. She was inconsistent and demanding. She was a nuisance, really, but she was there, and Nola took on the job of calming her down. This amused me, and I was grateful. Over time I became aware that Nola was – how shall I put it? – absorbing my personality. She sat close to me – very close – because she wanted to see the room and the things that happened in the way that I saw them. This was learning by osmosis as much as by anything else and I didn’t feel troubled by it because she had objectivity and a sense of humour that reassured me. I felt a little more valuable than I had before this interest developed. The weeks passed, Eddy almost dropped out, then came back, but was never at his best again, Nola kept the classes alive, and Sophie tried to make them as unstable as she was. Sometimes she sat facing me, though Nola stayed by my side. One morning, they were the first of the class to arrive, and Sophie told me she might be leaving soon because she was pregnant. I looked at her in surprise. ‘It was real bad luck,’ she said, ‘we only ever did it once!’ I didn’t believe that for a moment and I sensed that Nola, standing not far from me, knew it wasn’t true.

I dare say I asked Sophie if her family knew, and if the boy’s family knew, then the other students arrived and the conversation was cut off. This was one drama Sophie didn’t want to publicise. I felt Nola’s closeness quite strongly that morning, as if by merging herself into me she could cut off the emotional demands her friend was making. The year rolled on, Sophie left, Eddie handed in a thin, disappointing folder of work and I knew he wouldn’t pass, while Nola flourished. The year ended, the weeks of holiday rolled by, then the following year started. Busy, busy, busy. One lunchtime I came back from the bank in High Street, parked my car in its usual spot and got out. Coming toward me in the street was Nola. She’d been to the general office to collect something, and she was on her way home again. I had no idea where she lived. I said it was lovely to see her, but I really couldn’t stop to talk because there were heaps of things I had to sort out as soon as I got back to my department. To my surprise, she put her arms around me. If this sounds erotic, it didn’t seem so to me. I think she was curious. Then she let me go, and I crossed Saint Georges Road. Was I surprised? I decided that I wasn’t. The embrace had been consistent with sitting close to me, the previous year. It was also, I thought, a letting go. Then I asked myself how I felt about what had happened, and I felt pleased, and serene. I had no sympathy at all with teachers who got themselves into relationships with students, but I didn’t tax myself with this. Nonetheless, the incident stuck in my mind as something to try to work out, and there it stayed for two or three years until another something happened.

I was driving up Waterdale Road in Ivanhoe, my home suburb, approaching the intersection with Banksia Street. I drew level with a large black car; level, because it was going straight ahead, and I was turning right. I glanced at the driver of the other car and it was Nola. She glanced across, and, recognising me, she grinned. I don’t actually remember my reaction but I’m sure I smiled. I must have smiled! Then our cars went on (Nola) and right (me). This final meeting must sound trifling, petty, insignificant, but I realised as I drove up Banksia Street in the direction of Heidelberg, that I felt fulfilled. Something had been completed, and it had been a joy to us both.

The Director’s Chair

I want to swing now to another experience, closer to the end of my teaching days, which gave me, perhaps, the same instruction in reverse. The education system at the time allocated schools a certain number of special duties allowances, known as SDAs; the school decided how it would allocate these duties, then invited its staff to apply. SDAs were sought after because they were signs of approval for teachers hoping to gain promotion. I was head of humanities at Preston TAFE, but the department had some years previously decided that it would operate on democratic lines, which meant meetings, motions, and votes. Admirable as this may have been in theory and for much of the time in practice, it could be irksome for the head of department who frequently found himself squeezed between a department which had told him what it wanted and an administration that expected him to exercise authority over those in his ranks. (As one of my friends likes to say, ‘You can’t win; there’s only several ways of losing!’) So the SDA positions had been advertised and three, I think, members of my (‘my’?) department had applied. The applications went before a committee and the committee, meeting in the director’s office, though he wasn’t there, had narrowed the three to two, after which they called in the department head. Me. It was explained that the committee was seeking my advice on the matter and I was invited to sit in the only empty chair.

This was the director’s chair. I went around his desk to take the seat, and found that, out of sight of anyone else in the room, because hidden by the desk, was a low platform on which the chair rested. I sat, looking over, no, looking down on, the SDA committee, including its chairman, the deputy director, a man I liked. They asked me to comment on the two contenders. Both, I said, would be good in the position. I was asked further questions. My answers were so even-handed as to be exasperating. My position felt doubly compromised. I had only to give a wink or a nod for one candidate and that one would have got the position, but it was not lost on me that word about my summons before the committee would get back to my colleagues and I would have been accused of undemocratic behaviour. Our proceedings were explicitly designed to stop the head of department from having the powers that had been thrust on me by the committee. And there was the matter of the director’s chair. I’d never sat in it before, so I’d never known about its height advantage. The director spent his day looking down on those who came to see him. I’d been to see him on any number of occasions, and I thought I knew his wiles, tricks and threats about as well as anyone could.

But there was a trick I didn’t know. I thought about that seat, that height advantage, for days. I’m thinking about it now. What did it mean? What did it give him that others, unaware of his advantage, didn’t know? I think it added a certain mystique of authority to the director, a little extra something on top of the aura of his office, with secretary outside and private toilet hidden off. The director, in his chair, had something you didn’t know about; his desk was wide enough for the added height not to be apparent. This meant that the advantage was in the director’s mind. He wasn’t seeing you in quite the way you thought. How long had that little platform been there? Who’d installed it? I was quite prepared to believe that the director of my time had done this but had to accept that it was probably one of his predecessors. Who, and why? I knew I’d never know, but it made me aware of a weakness in myself that I hadn’t recognised until then. It wasn’t part of my temperament to challenge authority. I’d never rebelled against my parents, partly because they’d made me autonomous from an early age so there was no need, and partly because by the time I reached the age when boys rebel, I was part of the system in force at Melbourne Grammar, and there was no beating that: one would have been foolish to try. Besides, as I’d seen in my Trinity years, the rewards for conformity, or going along, were considerable. I’d seen this when I’d started to teach in Bairnsdale; men who were far more mature than I were carrying chips on their shoulder that I didn’t have. My upbringing, and my schooling, had given me a certainty that there was nobody on earth possessed of superior status to mine. Courtesy and consideration come much more easily to those who know they don’t have to touch their forelock here and there, and I, and the boys who’d worn the navy blue with me, had that pride and confidence.

Many of my Preston colleagues saw things differently, via a critique of society emanating from their political allegiances and their ideologies stemming from a variety of writers who can be summed up by mentioning Marx and Freud: the society and the mind. To someone of my outlook, these ideologies chipped away at society’s beliefs; to my more radical colleagues, educated differently, and made more different by their reading and thinking, the ideas I called ‘society’s beliefs’ were in fact the methods by which society was deceived into accepting a regime, of power, of ideas, that benefited a relatively small number at the top, while whatever was left over trickled down to the levels on which the masses existed. To me, too, this was obvious, but my way of dealing with the situation was, I dare say, typical of my upbringing. I’ve already quoted my slogan, ‘Fight only the battles you can win; occupy other ground surreptitiously’. For me, the existence of a program designed to get people into university who would otherwise never have got there, with the consequent opening up of universities themselves, was a significant piece of surreptitious occupation. For a number of my colleagues, it wasn’t enough. They looked for opportunities for confrontation, which meant that their wishes, their instinctive policies, contradicted my innermost tendencies, as quoted above. I was prepared to be as stubborn, perhaps devious as was necessary to achieve long term goals, but I was too proud to fight and lose.

Emily at Preston

The tertiary orientation programs I’ve referred to were also taught in a small number of local technical schools, and when teachers assembled at the end of the year for the assessment of students’ folders, a division opened up between the now-TAFE teachers at Preston and the junior tech. teachers from elsewhere. The latter felt their main job was to encourage, to be sympathetic, and to applaud whenever anything quarter-way decent was achieved. Preston people were aware that the students we sent on to university had to do well when they got there, otherwise we would soon be out of a job. Thus we returned to that old difficulty in teaching – handling the transition from support and encouragement, with the teacher behind and beside the student, taking the student’s part, and, the other inescapable role of the teacher, laying down society’s demands for young people to meet. Teaching at the year 12 level, we were, Preston teachers knew, inescapably on society’s side, however much encouragement, sympathy and support we might give.

I think we reconciled ourselves to this position by thinking of ourselves as giving the students a way out of a society which would drag them down if they didn’t rise to its challenges. So we were in the position of being critical, perhaps fiercely so, of the surrounding society, while thinking that any student who couldn’t find a way to a reasonable sort of island in a stormy sea was probably beyond help. The trap with this attitude was that it allowed teachers to feel that they occupied a moral high ground, which is always dangerous. I don’t think we ever solved that problem; indeed, the more successful we became at our work, the more the danger infected us.

Looking back now on those early years of tertiary preparation work, I see any number of messes and muddles which came about because we were still struggling toward a professional way of working, but I also remember many happy hours in what had once been a trade workshop, seated around clusters of tables, talking our way through books and ideas on a level we’d never expected to reach. I was taking a unit on the poetry of Bruce Dawe with a group whose parents, many of them, had been new arrivals not so many years before, and I thought there was enough social commentary in Dawe’s poetry to make his themes as recognisable as his distinctive voice. One of my students was a Greek lad whom I called Lennie Pascoe because he resembled a New South Wales cricketer of that name. Lennie, as I shall call him, loved Bruce Dawe’s poems, and as we read them, one after another, his gasps and murmurs told me that doors were opening in his mind. We read homecoming:

All day, day after day, they’re bringing them home,

they’re picking them up, those they can find, and bringing them home,

they’re bringing them in, piled on the hulls of Grants, in trucks, in convoys,

they’re zipping them up in green plastic bags,

they’re tagging them now in Saigon, in the mortuary coolness

they’re giving them names …

The Vietnam war had divided Australia, and like many of my colleagues I had taken part in marches through our city, calling for the war to end, and I don’t think Lennie or the others in his group had ever imagined that poetry could be so pressing. Or so funny:

When children are born in Victoria

they are wrapped in the club-colours, laid in beribboned cots,

having already begun a lifetime’s barracking.

Carn, they cry, Carn … feebly at first

while parents playfully tussle with them

for possession of a rusk: Ah, he’s a little Tiger! (And they are …)

One that never failed to move us was Dawe’s elegy for drowned children:

Yet even an old acquisitive king must feel

Remorse poisoning his joy, since he allows

Particular boys each evening to arouse

From leaden-lidded sleep, softly to steal

Away to the whispering shore, there to plunge in,

And fluid as porpoises swim upward, upward through the dividing

Waters until, soon, each back home is striding

Over thresholds of welcome dream with wet and moonlit skin.

Every poet is a voice and none can claim to be more authentic than the next, but I felt that Bruce Dawe had shown Lennie’s group that there were aspects of their society that they hadn’t known existed until his poetry had been put before them. I felt proud of playing my part in this, and proudest of all when a similar thing happened with the American Emily Dickinson.

There were, I think, sixteen of us in one of the smaller rooms. We squeezed in with no room to spare. I told them a little about Emily’s reclusive life, then we began to read. It was a wintry day outside, and windy. Clouds skittered across the sky, giving us alternating bursts of light and gloom on the tall, industrial window. Leaves of two large bushes brushed against the pane in the wind; we were warm inside, from a heater. Something about the day gave us empathy with the writing, the miracle happened and it seemed that we were inside the poetry and it was in us. I chose carefully the order in which we read the poems, making sure that one led to the next. Towards the end of the session we came to …

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For his Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess – in the Ring –

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain –

We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us –

The Dews drew quivering and chill –

For only Gossamer, my Gown –

My Tippet – only Tulle –

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground –

The Roof was scarcely visible –

The Cornice – in the Ground –

Since then – ‘tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity –

We sat back, silent. We looked at our bits of paper, and the leaves brushing against the glass, sunlit, then darkened again. Nobody said anything. We got out of our chairs, nodded to each other, and left the room. Emily’s spirit had been with us, speaking, and there was no need for us to talk. What had we to say, when a great poet had been present in our room?

The writing of this book:

I’ve already commented on the writing of the book (All the Way to Z) which is the source of the extracts making up this mini-mag so I’ll comment only on what led me to put this selection together. I’d attended a couple of meetings in Bairnsdale (2014, 2015) to do with the possible creation of an East Gippsland writers group and had had copies printed of an earlier essay (Gippsland’s first great book) with the intention of giving them to those who attended the meeting at which I hoped such a group would be formed. This reminded me that I started publishing mini-mags several years earlier as a means of getting my work in front of hundreds, even thousands, of people who would otherwise not have been aware of it. To put it another way, a mini-mag was a means of advertising my website so I started looking through my earlier writings to see if other selections could be republished in the mini-mag format. The piece about Emily Dickinson seemed a natural companion for my appreciation of Eve Langley, so I culled through the book of which it was a part and chose the extracts now reprinted as a good setting for Emily’s arrival in a place the reclusive poet would never have heard of.