These Fields Are Mine!

Written by Chester Eagle

Designed by Chester Eagle

Layout by Karen Wilson

200 copies printed by Design To Print

Circa 5,520 words

Electronic publication by Trojan Press (2015)

These Fields Are Mine!

I propose to do something quite simple. I’m going to present two passages, each describing an incident of war whereby a non-combatant (in each case a woman) is affected by ‘well-intentioned’ preparations for conflict. Each passage will be followed by some brief notes to help the reader grasp the import of what’s been presented, after which I will take the discussion a little further according to my readings of these passages, and the books they come from. The first passage is from The Middle Parts of Fortune, by Frederic Manning, published by Peter Davies, London, 1929 (with a lightly expurgated version known as Her Privates We following in 1930): both versions offer this account of Allied soldiers practising, in 1916, a forthcoming attack on the German lines.

Other important people on horseback, even the most important of them all, on a grey, arrived, and grouped themselves impressively, as if for a portrait. There followed some discussion, first apparently as to the number of the Colonel’s runners, and then as to why they were not within the imaginary trenches as marked out by the tapes. The Colonel remained imperturbable, only saying, in a tone of mild protest, that they would be in the trenches on the day, though there were some advantages in separating them from the other men at the moment. They were all moving forward at a foot’s pace, and apparently the Olympian masters of their fate were willing to admit the validity of the Colonel’s argument, when there was a sudden diversion.

They were passing a small cottage, little more than a hovel, where three cows were tethered to pasture on some rough grass; and the tapes passed diagonally across a square patch of sown clover, dark and green in comparison with the dryer herbage beside it. This was the track taken by a platoon of A Company under Mr Sothern; and as the first few men were crossing the clover, the door of the hovel was flung open, and an infuriated woman appeared.

‘Ces champs sont à moi!’ she screamed, and this was the prelude to a withering fire of invective, which promised to be inexhaustible. It gave a slight tinge of reality to operations which were degenerating into a series of co-ordinated drill movements. The men of destiny looked at her, and then at one another. It was a contingency which had not been foreseen by the Staff, whose intention it had been to represent, under ideal conditions, an attack on the village of Serre, several miles away, where this particular lady did not live. They felt, therefore, that they had been justified in ignoring her existence. She was evidently of a different opinion. She was a very stubborn piece of reality, as she stood there with her black skirt and red petticoat kilted up to her knees, her grey stockings, and her ploughman’s boots. She had a perfect genius for vituperation, which she directed against the men, the officers and the état-major, with a fine impartiality. The barrage was effective; and the men, with a thoroughly English respect for the rights of property, hesitated to commit any further trespass.

‘Send someone to speak to that woman,’ said the Divisional General to a Brigadier; and the Brigadier passed on the order to the Colonel, and the Colonel to the Adjutant, and the Adjutant to Mr Sothern, who, remembering that Bourne had once interpreted his wishes to an old woman in Méaulte when he wanted a broom, now thrust him into the forefront of the battle. That is what is called, in the British Army, the chain of responsibility, which means that all responsibility for the errors of their superior officers, is borne eventually by private soldiers in the ranks.

For a moment she turned all her hostility on Bourne, prepared to defend her title at the cost of her life, if need should arise. He told her that she would be paid in full for any damage done by the troops; but she replied, very reasonably for all her heat, that her clover was all the feed she had for her cows through the winter, and that mere payment for the clover would be inadequate compensation for the loss of her cows. Bourne knew her difficulties; it was difficult enough, through lack of transport, for these unfortunate peasants to bring up provisions for themselves. He suggested, desperately, to Mr Sothern and the adjutant, that the men should leave the tapes and return to them on the other side of the clover. The adjutant was equal to the situation; and, as the rest of the men doubled around the patch to regain the tapes, and their correct position, the General, with all his splendid satellites, moved discreetly away to another part of the field. One of the men shouted out something about ‘les Allemands’ to the victorious lady, and she threw discretion to the winds.

‘Les Allemands sont très bons!’ she shrieked at him.

An aeroplane suddenly appeared in the sky, and, circling over them, signalled with a klaxon horn. The men moved slowly away from her beloved fields, and the tired woman went back into the hovel, and slammed the door on a monstrous world.

The character Bourne in the book may, I think, be regarded as representing Manning himself, although I note that Michael Howard, in contributing an introduction to the 1977 edition of Manning’s book, has this to say: ‘the author has distanced himself from his own experience as all writers must who wish to create a true work of art. He only partly identifies himself with his hero, the solitary, enigmatic Bourne. Bourne is significant only as the observer of, and spokesman for, a group of men bound together in a common effort to endure the unendurable.’ While I accept this view, I do so with some caution, because I think that Manning, whose life until the moment of joining the English army had largely been one of withdrawal, managed to maintain some distance between himself and the circumstances surrounding him. He went to the war, in my view, as much from curiosity as anything else; he was an observer at least as much as a participant, and it was only at the end of the 1920s, when his friend and eventual publisher, Peter Davies, urged him to sit down and write, that he became the spokesman for front line soldiers that readers have long admired.

The only other comment I wish to make on Manning before we move to a second piece of war writing concerns the matter of rank. Manning might easily have used his background and social connections to get officer training before going to war, but he chose to enlist as a private; this put him in the closest proximity to the soldiers who bore the brunt of the ghastly trench warfare, and it was only after a few months of seeing the fighting that he allowed himself to accept the officer training which provided him with an exit from the trenches. He spent the rest of the war well away from the shooting and shelling that he would eventually write about.

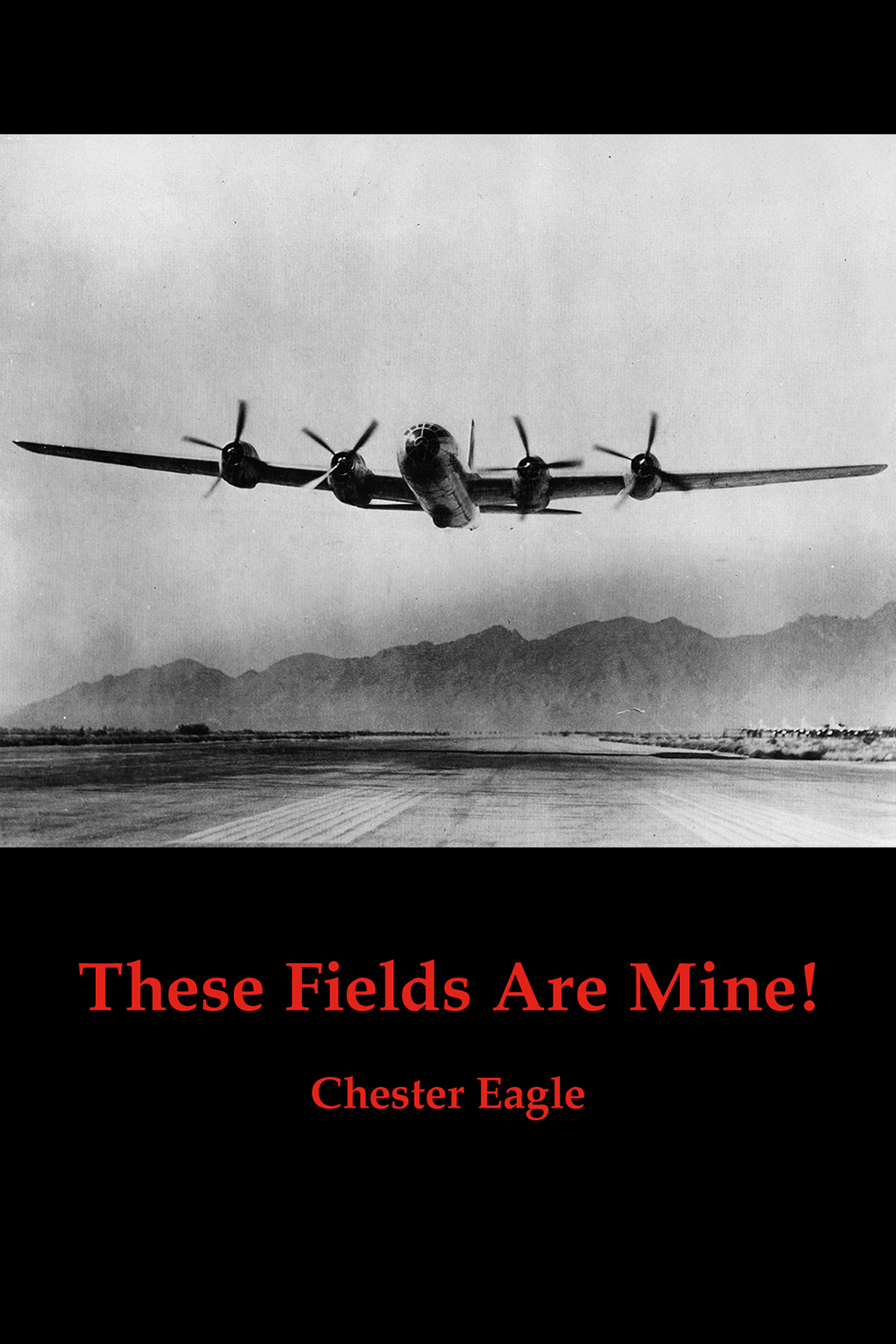

I would like to move now to a passage from Guard of Honour, by James Gould Cozzens, first published in 1949 by Longmans Green and Co. Ltd, London. The action of this book takes place over the course of three days at an Army Air Force base in the state of Florida, USA, and the airmen and soldiers at this base are being readied to play a part in World War II.

“Let me tell you something, which you will treat as top secret,” General Nichols said, still smiling. “I was at the conference at Quebec last month. A certain intelligence service, which seems to be smarter than ours, laid before the meeting some information of great interest. It was a minute of the specific terms on which one of our important allies offered to join the Axis in 1940; and on which they offered, this year, to make a separate peace. They were turned down both times because the Germans thought the terms too high—”

They were at the gates of the Area. All other traffic had been halted and moved over to the side. The guard was drawn up at attention by the gate house. General Nichols touched his cap, and they went through the arch. He said: ‘We don’t know whether the offer, or a modification of it, still stands; but it is obvious that we would be unwise to trust these friends or count on them very far. If the Germans changed their minds, we might have to throw away our operational planning for next year.” He laughed quietly.

“Yes,” Colonel Mowbray said. He sat a moment, his mouth open in brooding surmise. “Yes, I see that could be pretty bad,” he said.

General Nichols said, “It reminds me in some ways of a situation that developed at Keesler Field a few weeks ago when I was down there. Off the shore, there are a couple of small islands, a few miles out in the gulf. One of them is uninhabited, and it had been used for some time as a gunnery range for fighter planes. The other island belongs to an old woman, somewhat eccentric, who lives there alone; has a vegetable garden, some chickens, a cow. There is a house on it, and a barn; but they don’t amount to much.”

General Nichols cleared his throat. “Well, it happens that, from the air, it looks a good deal like the other island, about the same size and shape; and they’re right there together. As I say, the house and barn don’t amount to much, and the other island had a couple of sheds on it, which I think fishermen used for something sometime. The planes would fire at these old sheds. I suppose it was remarkable that it hadn’t happened before; but at any rate, one evening a pilot who wasn’t very familiar with the range took out a P-Thirty-nine to try a newly installed cannon. He made a run on the island, put his sights on this shed, and opened up. It happened to be the wrong island, and the shed was the barn, and the old woman was in the barn, milking the cow.”

General Nichols shook his head. “It was good shooting. The pilot lobbed in four or five thirty-seven-mm shells, broke the roof all to bits, scored two direct hits on the cow, which just disintegrated. My, it was a mess!”

Colonel Mowbray said, “What happened to the old woman?”

Mournfully, General Nichols said, “Pop, she was left holding the bag.”

Cozzens, like Manning, was a very withdrawn man. The TIME article (September 2, 1957) introducing his best known novel, By Love Possessed, presented him as a stay-at-home house-husband of his literary agent wife, Sylvia Bernice Cozzens (née Baumgarten). He did, however, work in the US Army Air Force from 1943 to 1945, and the passage quoted is from the novel which drew on that period of his life. Both By Love Possessed and Guard of Honour contain a central figure (Arthur Winner in the former, Colonel Ross in the latter) who does his best to manage events and hold things together in ways that would seem appropriate and even necessary for someone like Cozzens the resident of Lambertville Pennsylvania, but Cozzens the novelist is well aware that the world presents a variety of human types, not to mention uncontrollable happenings, and the difference between the way the world is seen and managed by Arthur Winner and/or Colonel Ross and the way things actually happen is what provides Cozzens’ books with their fascination, their richness of detail, and the wisdom they offer to readers.

Another feature of these two books deserving mention is that each, although substantial in length and scope, covers events within a limited time frame – three days in Guard of Honour and forty-nine hours in By Love Possessed. This restriction requires Cozzens to use an intensity of analysis and detached control of narrative which has caused his writing to be admired by some, scorned by others. He was rarely a popular writer in his day, is now largely forgotten and has had little influence on the way other Americans write or think about their writing.

Detachment and a high degree of objectivity were characteristic of both Manning and Cozzens. Both watched closely and considered what they saw. In Manning’s case this detachment went a little further because he was an Australian in the English army and Australian commentators have remarked on the handful of occasions where his origins can be detected, or at least suspected, in his presentation. A similar detachment can be found by observing that characters in Guard of Honour commonly refer to Colonel Ross by his peace-time title of ‘Judge’, thus respecting the fact that he is demonstrating the qualities of his former occupation as he carries out his military duties. Both Colonel Ross and Private Bourne are valued by their fellow soldiers for this quality of detachment: war is so stressful that anyone who can maintain good judgement is listened to. One of the central preoccupations of Manning’s book is the thinking of the common soldiers as they try to work out what it is they are doing, what is being done to them, by whom, and ultimately, why? Manning listened closely to his fellow men and his respect is apparent in his comparison of what they say about their situation with the soldiers of Shakespeare’s plays and what they said about theirs, centuries before. At the top of Manning’s first chapter we read these words: ‘By my troth, I care not; a man can die but once; we owe God a death … and let it go which way it will, he that dies this year is quit for the next.’ Manning’s boldness in putting his soldiers and what he writes about them into the context of England’s greatest writer has the effect of broadening his subject matter from the war in which he took part to all wars, to the nature of war itself. To conduct a war requires endless organisation. Societies have to function differently if they are to wage war, the changes required may be huge, and they are most easily visible in the way an army operates, notably in the idea of a chain of command. Those at the top of such a chain have a freedom denied to those beneath them, who must follow orders (or do their best to do so!), but this freedom is encumbered by an enormous responsibility to reduce as far as possible the loss of lives and destruction of cities and countryside which are an inevitable part of war. Those at the bottom are in almost the opposite situation. They have no freedom to decide what they will do or when, where and how they will do it, but, being treated as almost mindless executors of other men’s orders, they bear little responsibility for what happens. This leaves them open to speculate, as Manning’s soldiers do frequently and at length.

The French peasant woman, perhaps inadvertently, exploits this gap between the viewpoints of the high and the lowly-ranked sections of the British Army when she screams ‘These fields are mine!’ at the soldiers crossing her land. Manning says they have a thoroughly English respect for property, and since she is clearly no respecter of rank, she causes the lordly men on horseback to abdicate their responsibility for what’s happening by sending someone (of lower rank, naturally) to ‘speak to that woman’. The job falls to Bourne, and Manning observes that this is what happens in the army: responsibility for anything going wrong is passed downwards as quickly as possible. Bourne finds a solution to the problem, but not before the furious peasant tells the soldiers that ‘The Germans are very good!’ Since the men who are crossing her land are going to face the Germans in a day or two they have to swallow the insult and move away from her domain. It may be worthless to soldiers and their officers on horseback, but it is hers, after all.

How does she get away with it? Because a face-saving solution to the problem is found (by someone of no importance except that he will one day describe it in a book); because the men on horseback, whose rank means they can’t accept disobedience, have had the sense to move away, leaving the matter to be sorted out at a level far beneath them; because her ownership of land is not something which this army-in-rehearsal wishes to challenge. She’s had a win – but how much good will it do her? If the larger battle with its trench-digging and endless shelling happens to move in her direction, her defiance will do nothing to stop it. The men on horseback don’t particularly want her land. It all depends on where the Germans move their forces. Even so, she won the day the moment the men of lower rank were stopped by the power of her invective. I think it might be surmised that the officers looking on couldn’t be sure whether the soldiers would move forward if ordered to do so: their ‘respect for property’, or is it the ferocity of her invective, has stopped them, and even an order might not make them restart. A victory indeed, and yet we have only to think of the vast areas of northern France laid waste by the same war to see that Manning’s peasant woman’s success in protecting her grass was a very rare thing. In the history of warfare Cozzens’ island dweller would have to be closer to typical.

Let us look at her, then. We only know about her because she’s mentioned by a senior officer in a light-hearted moment which I think we can take to be unusual. It’s the second story General Nichols tells his fellow officers and he says that his first story – which we will return to in a moment – reminds him of a situation that developed at a nearby base a few weeks earlier. For the life of me I cannot see why the general says this when the two tales are chalk and cheese to each other. They are in no way comparable. The first of the general’s stories might better be called a whisper that one of the nations in the alliance against Germany and Japan has been trying to make a separate peace, and even, at an earlier stage, to join the German side of the conflict. Which nation was that? Russia? The general doesn’t say, but he says that if this should come about then the Allied forces would have to abandon their current operational plans, that’s to say, they would have to fight the war very differently. This is rather more than a few shells hitting a cowshed! I think the general tells his second story because he needs to switch to something light-hearted after the gravity of what he says first. Am I right? Cozzens doesn’t say. Why not? Because, I think, he feels that the switch in the general’s talk will show the man leaping from something unpalatable to something which he expects to draw a laugh, and thus to relieve the burden of his thoughts. I think that if questioned, Cozzens would have said that happenings at a training base are as capable of revealing the workings of the military mind as events at the front line. I further think that anyone who reads the whole of Guard of Honour will see that his approach is justified. Such a reader will come upon an apparently inexplicable moment when General Beal (‘Bus’) gets into a fighter plane and flies as high and fast as the plane can go for no other reason that administering a large base is almost intolerable to a man of action such as he is, so he has to get away from his desk, indeed get away from the earth, before he can settle his mind back to his administrative job. Cozzens doesn’t bother to explicate this foible. He tells us what General Beal did and leaves us to interpret for ourselves.

General Nichols changes the subject because he needs to. Something too awful to contemplate is replaced in his mind by something so ridiculous that it will surely draw a laugh. The object of his laughter, and probably the reader’s too, is another woman, remarkably similar to Manning’s peasant, scratching out a living of sorts from an otherwise unwanted scrap of land. What makes her dissimilar is that she can’t confront the pilots who strafe the neighbouring island. They’re too high in the sky, too fast and too noisy to hear her if she feels like shouting. She would surely have been aware of her danger, since it’s clear from the general’s narrative that use of the other island as a bombing range has been common; ‘it’s remarkable that it hadn’t happened before’. The inevitable mistake occurs, the shed is destroyed and the cow becomes ‘a mess’. What happened to the old woman? She was left holding ‘the bag’; I must presume this means the cow’s udder and teats, the source of its milk. The general’s story ridicules the female of all species. Cozzens ends the section at the point where my quotation leaves it, and begins a newly-numbered section. The island woman is left with a roofless shed, a mess and ‘the bag’, and she, like Manning’s peasant, disappears from our consideration.

Is that the end of them, then?

No, because writers write books and readers read them, and while it’s true that we may put down a book and never pick it up again, a good book engages our mind and its effects may last a long time afterwards, perhaps even a lifetime. Books, and here I am thinking of works of fiction, offer us not so much facts, although they may do that, as points of view. They show us how to see events, personalities and/or historical periods in ways that we might not have considered before. The writer is saying to the reader that if s/he looks at things in the way the writer is proposing then things will, or may, look different. It is wrong, I think, or perhaps simply too shallow, to think of reading as entertainment. Any book worth reading, any film worth viewing, proposes a way of seeing, a way of thinking about its subject. Frederic Manning gives us the battles of northern France in 1916 as the common soldiers in the front line experienced them. World War I gave rise to many such accounts, written in a range of languages – English, German, French, Russian and no doubt others. This happened because it was a war the likes of which had not been seen before, and human beings had to work out what they had done. New understandings had to be developed. Memoirs of commanders were still published and read, but the common soldiers’ experience had to be taken into account because, with the rise of the nation state, and the induction into armies of their citizens when required, the winning and losing of wars ultimately depended on public opinion back home, behind the lines and, of course, the qualities of normal civilian life which the men, now soldiers, embodied and relied on. Manning again:

Bourne sometimes wondered how far a battalion recruited mainly from London, or from one of the provincial cities, differed from his own, the men of which came from farms, and, in a lesser measure, from mining villages of no great importance. The simplicity of their outlook gave them a certain dignity, because it was free from irrelevances. Certainly they had all the appetites of men, and in the aggregate, probably embodied most of the vices to which flesh is prone; but they were not preoccupied with their vices and appetites, they could master them with rather a splendid indifference; and even sensuality has its aspect of tenderness. These apparently rude and brutal natures comforted, encouraged and reconciled each other to fate, with a tenderness and tact which was more moving than anything in life. They had nothing; not even their own bodies, which had become mere implements of warfare. They turned from the wreckage and misery of life to an empty heaven, and from an empty heaven to the silence of their own hearts. They had been brought to the last extremity of hope, and yet they put their hands on each other’s shoulders and said with a passionate conviction that it would be all right, though they had faith in nothing, but in themselves and in each other.

This passage offers us another, perhaps final, reason why the soldiers refrained from marching across the peasant woman’s grass: her position was not so very different from their own. War might wipe out any of them at any time, soldier or peasant. Yet she did make one claim that the soldiers could not: Ces champs sont à moi! These fields are mine! If she loses her grass, she loses her cows; if she loses her cows she loses her livelihood, which she is trying to maintain despite the war rageing around her. What will the soldiers do? Side with the war against her? Or side with her against the war, of which they themselves are part? Their officers are watching. They take her side by standing still. By doing nothing, they are doing a great deal. Orders come down: ‘Speak to that woman.’ Who is to say what? According to Manning, the highest officer in the field is passing responsibility down to the lower ranks. Do something. Do anything. Get us out of this.

A way is found. The troops move around the grass. Humanity redeems itself, ever so slightly. The men move on. The signal to end the rehearsal is sounded from a plane. Everyone goes back to wherever in the lines is their place. The attack, no doubt, will take place as planned.

This leads me to ask – how did things end at the Florida base? Did the US Army Air Force repair the woman’s shed, replace the murdered cow? If so, who paid? Did a high-ranking officer sign a slip of paper authorising compensation, or was the errant pilot forced to pull dollars out of his pocket? Did anyone ever apologise? If they did, was it by letter, or did someone make a trip to the island to say to the injured party – This island is yours, and our pilots have been instructed not to fire at it? We’re not told. I’ve already commented on Cozzens’ objectivity. I think we can read the US Army Air Force’s attitudes into the way Cozzens presents his story. If there ever was an apology, or payment by way of compensation, it would be a mere detail in the daily operation of the base. General Nichols would think it obvious that winning the war was vastly more important than the accidental death of a cow. The USAAF pilot, as he pointed out, had done some ‘good shooting’. The pilot, like the cow and the island woman, disappear from the book, which goes on for another 376 pages. America has been attacked. Its Pacific fleet has been destroyed at Pearl Harbour, but that was only round one. The United States won’t be caught napping again. The book ends with General Nichols flying back to Washington, seen off by General Bus Beal and Colonel Ross, the man who tries to manage the world as Cozzens feels it needs to be managed. They chat, these two officers, about various problems and difficulties, and they reach an understanding when the general slaps the Colonel’s shoulder and says, ‘I’ll do the best I can, Judge; and you do the best you can, and who’s going to do it better?’ Their moment of understanding is interrupted by the General’s wife tooting a car horn and calling out that she and others in the car want to go home. The general is agreeable: “Why not?” General Beal said. “Shall we go, Judge?” But Cozzens doesn’t let his book end without an expression of confidence in all that he’s shown us:

Yet he stood a moment, his eyes narrowed, raised to the night. The position lights of the northbound plane could still be made out by their steady movement if you knew where to look. The sound of engines faded on the higher air, merging peacefully in silence. Now in the calm night and the vast sky, the lights lost themselves, no more than stars among the innumerable stars.

Books are generally categorised as fiction or non-fiction. This is a strange dichotomy, suggesting that fiction can be defined, should a definition be required, but the alternative – anything that isn’t fiction – can’t. This suggests, again, that we know what fiction is, but can’t provide a simple name for its alternative. ‘Non-fiction’ means no more than anything and everything else. Not very helpful, is it! Perhaps we are in this awkward position because we think that writers of fiction give play to their imaginations, while other writers don’t. A moment’s thought will show how silly that is. Even the most scholarly of historians or the most disciplined of scientists must use their imaginations. The same applies to Manning and Cozzens, both of them writers who produced work of remarkable objectivity. This word – objectivity – is generally regarded as being opposed in meaning to imagination. Imagination is commonly thought of as belonging to children and those unreconstructed types who provide adults with narratives which give us pleasure, amusement, or possibly instruction of some sort. This is an unsatisfactory view. Imagination is part and parcel of our everyday thinking and without it our lives would be about as interesting as our shopping lists. Imagining is part and parcel of considering the future and almost inseparable from remembering. It is the way that our remembering is done. That is to say, if we wish to report on something, we must engage in the business of recall. What happened, we ask ourselves, and at the same time we further ask ourselves, what was it like? Enter imagination, straight away and at once. What was it like? To answer that question we must consult our feelings. But our feelings, no matter how accurately we remember them, are not quite the same the second time we feel them. To have them act inside us for a second time we must re-create them. No sooner do we start to do this than we realise that we are re-creating not only our own feelings, thoughts, hopes and fears but those of others who were present at the time. We are, I think you must admit, in need of imagination and insight if we are to know what else was happening beside the things that directly and immediately affected us. This is obvious. If I claim to tell you what happened during a battle in which I participated, my account will be thin and miserable if I don’t use my imagination and my insight to give you more than my own – no doubt very minor – personal experiences.

Let us look one last time, then, at our two accounts, and see what they are giving us. I think, finally, that Manning is giving us a look at war by a man peculiarly well-fitted to understand it. War is a mass action, but the mass is composed of individuals, each of them experiencing it slightly differently. To know what the battle – or in Manning’s case, the rehearsal for battle – is like, we need to see into the hearts minds and souls of everyone present. Since it is hardly possible to do this in a piece of readable prose, he selects the officers on horseback, the adjutant, Mr Sothern, Bourne and all the other private soldiers, and last and central, the peasant woman. With these actors he re-enacts the drama so that we can take it from his imagination and into ours. To do this he needs to use his prose like a jeweller, and he does. Cozzens’ aim is different. The American mind was not as exhausted by centuries of warfare as the Europeans with their long history stretching back. In the aftermath of what they regarded as the treachery of the Pearl Harbour attack, the Americans gathered themselves inside the traditions of their own new civilisation, an improvement on the old as they saw things, and they determined to crush those who had humiliated them. They saw themselves as being on the right side, struggling with an evil adversary who needed to be destroyed. As we all know, this was done. Cozzens’ book ends, as we have seen, with the lights of the plane taking General Nichols back to Washington merging with the stars. Cozzens was making his meaning very clear. Great writers can.

The writing of this book:

I have long admired Frederic Manning’s classic WW1 book, and, on a recent re-reading of books by James Gould Cozzens, I noticed in Guard of Honour (first published 1949) an incident which reminded me of a passage in The Middle Parts of Fortune. Both books featured a moment when an isolated woman, farming on the humblest scale, had her agricultural routine interrupted by military preparations. It seemed to me that a reader sympathetic to the purposes of Manning and of Cozzens could not fail to see that the two writers used similar incidents for entirely different purposes. What were these purposes and how could they be made apparent? I set myself to answer these questions. The task was easy enough to define, not so easy to achieve. I don’t much like people – including other writers – explicating the meaning of first rate writers’ work, on the basis that if Shakespeare said ‘To be or not to be, that is the question’ then, if Shakespeare is as great a writer as we like to say he is, it is simply not possible to put his thought in other words. My task, then, or so it seemed to me, was first to select the passages from my two writers, then to give them a setting which made apparent to the reader the similarities and differences in the two writers’ intentions. This is what I attempted to do.